Emotional well-being through musical play

by

Johannes Dreyer

Bachelor of Audio Production (BAP)

Graduate Project Exegesis

Presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Creative Industries

SAE Creative Media Institute,

December 2019

Key Words

Self-Expression; Wellness; Music and Emotion; Emotional Recognition; Music Technology; iPad technology; User Design; Interaction Design; Children.

Abstract

Music and emotion have always held the interest of a diverse range of scholarly fields, and in this exegesis, I frame some cultural and physiological theories relating to the emotional and cognitive impacts of music to help understand how music is able to employ such a strong emotional connection with listeners. My multi-method research project is focused on the interaction design of music technology to create an interactive wellbeing tool for school-aged children, aiming to assist with emotional recognition and creative play.

My Graduate project focussed on the design and implementation of an online music creation and wellbeing tool, for school-aged children. The working version is embedded further down this page, please have a play.

Introduction

“What we have said makes it clear that music possesses the power of producing an effect on the character of the soul.” (Aristotle, Politics)

When we go to the gym, we are likely to listen to high energy dance music as it motivates and energises us, encouraging our bodies to move. By contrast, when we sit down to dinner, we are more likely to select something calming and unobtrusive. Lullabies put infants to sleep, work songs help ease the burden of repetitious physical labour and marches conjure bravery in preparation for war. Music is used to influence consumer spending in shopping malls (North & Hargreaves, 1997), and to curtail street violence and criminal behaviour (Hirsch, 2012). Indeed, there are many practical ways we make use of music in our everyday lives because we are acutely aware of its capacity to shape our experiences and behaviours.

The deep connection between music and human emotion is a well-researched topic that spans academic disciplines and research paradigms. According to music sociologist Tia DeNora, “music has organizational properties. It may serve as a resource in daily life, and it may be understood to have social ‘powers’ in relation to human social being” (De Nora, 2004, p. 151). Music technologist Jacek Grekow in his research states how “emotions are a dominant element in music, and they are the reason people listen to music so often.” (Grekow, 2018, p. 7) Psychology professor Patrik Juslin, in his book Musical Emotions Explained, states how “emotions—just like pieces of music—are dynamic processes. They unfold, linger, and then dissipate over time. Thus, most psychologists like to think of an emotion as a sequence of events” (Juslin, 2019, p. 46).

While my graduate project makes use of and aims to contribute to the interdisciplinary field of music and emotional research, the true impetus to pursue knowledge and make a creative contribution to the field is my beautiful nine-year-old stepdaughter, Sufjan. She has been diagnosed with high functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and as is the case with many neurodivergent people who share a similar diagnosis, Sufjan lives with sonic hypersensitivity. (Hughes, 2015)

In observing Sufjan and her neurotypical friends I was fascinated to note the differences in relation to her aural perceptions; the range of hearing and the emotional affect music has upon her. Our morning breakfast rituals are methodically organised around warnings for the use of the blender and coffee machine, and we’ve had to manage several movie nights due to soundtracks being a bit too ‘scary’.

As a music producer, DJ and educator I have been developing and teaching music production and engineering courses, and in the last five years, have had the privilege of mentoring special needs students diagnosed with ASD, Tourette’s, Cerebral Palsy and Down Syndrome. This is not a field that I sought out purposefully at first, but I continue to find myself presented with these mentoring opportunities.

This project capitalises on my sophisticated understanding of music production in combination with my professional experience as a lecturer and a mentor to address a need that I have identified through critical observation of my everyday lived experience. Carolyn Ellis in her heartful autoethnography paper explores how the autoethnographic process is quite a personal experience;

“an autoethnographers gaze, first through an ethnographic wide-angle lens, focusing outward on social and cultural aspects of their personal experience; then, they look inward, exposing a vulnerable self that is moved by and may move through, refract, and resist cultural interpretations (Ellis, 1999, p. 673).

My experience is not unique, so although I am focusing on that which I am intimately familiar with, the application will be wide-reaching and available to serve a range of emotional needs for both neurotypical and neurodivergent children.

Even though this project was inspired by my autistic daughter and there are references to Autism Spectrum Disorder, ASD is not a specific focus of this project, but instead, I am focussing on an analysis of a more general population and broad approach to emotional affect through musical interaction.

Research Statement

Design and develop an interactive music creation application that could serve as a wellbeing tool and assist with emotional recognition.

My project is an interactive musical experience; allowing the user to create and perform emotionally charged musical elements as an expressive, creative, and wellness tool. Through specific user interaction workflow, I aim to establish whether the user experienced an emotional change through this interaction.

I analysed the post-experience reflection of the user as it was captured anonymously in a database within the administration portal of the website. These findings and conclusions can be found in their relevant sections.

Research Methodology

This project is multimethod by design, utilising action research and design ethnography to inform the main research aspect and design thinking assisting with the functionality and design of the application. There are some overlapping elements within these approaches and I purposefully decided on this multimethod approach to utilise the strengths of each individual frameworks as well as the complimentary results they present as a whole. In particular, utilising design ethnography to strengthen the lack of research in the design thinking process.

Action Research

Morton-Cooper (2000) suggests that action research may not be a method of research at all or even a set of methods, but a way of approaching the study of human beings from a philosophical construct in which some form of sharing takes place within mutually supportive Evidence-based practice to researcher of the self-environments. It is, therefore, in this view, a critically reflexive approach to research in which claims of validity to knowledge within a particular domain can be examined and contested, which in this process help to generate new ways of thinking, seeing and acting. (Mckintosh, 2010, p. 32)

Morton-Cooper’s suggestion aligns well with my project and approach, one of the main aims of this project is to establish a human interaction and emotional response through music.

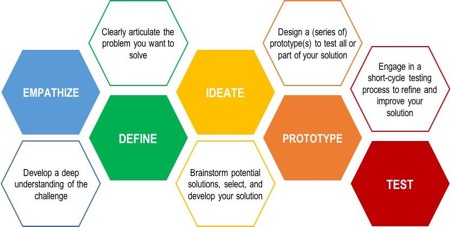

Design Thinking

“Design Thinking is a design methodology that provides a solution-based approach to solving problems.”

(Dam. R, Siang, T. 2019, para. 1)

Design Ethnography

The fundamental purpose of design ethnography is to establish the underlying problem, identify the best solution and then validate the solutions. The process of identifying what users need without them being able to articulate or perhaps even know what this need is is a crucial part of my design process and design ethnography guided me to a clearer understanding and outcome.

In order to understand the process of design ethnography David Travis & Philip Hodgson (2018) guide us with the following questions:

- What goals are users trying to achieve?

- How do they currently do it?

- What parts do they love or hate?

- What difficulties do they experience along the way?

- What workarounds do they use? (Travis, D. Hodgson, P. 2018, para. 4)

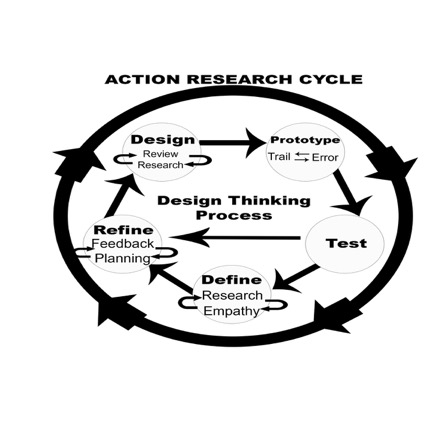

This process can easily be related to the design thinking stages of empathy and research and as a result, directly informs my framework and methodology. My iterative action research cycle broadly encompassed each one of the design thinking stages and subsequently, there were iterative cycles embedded within these stages.

Fig. 2 shows a simplified flow chart of my process and the stages I worked through to eventually end with a refined and efficient product. A simplified definition for action research is a process of experiment and observation, and design thinking is based around the establishment of needs, design, prototyping, testing and refinement. Design ethnography is the process of research, testing and refining our design. These three processes were very complimentary and became the overarching framework throughout the whole project.

As Fig. 2 shows, during each stage, there will be some form of iterative cycles where my research, problem or design will be refined and retested. Examples include:

- During the Define / Refine phases; the process of empathy and research cycles in conjunction with feedback and planning established a more focussed definition and scope for the project as well as an overall better design

- During the Design / Prototype / Test phases; cycles of review and research/trial and error informed and refined the research, product design and user experience, which was then facilitated through design ethnography.

Creative Component

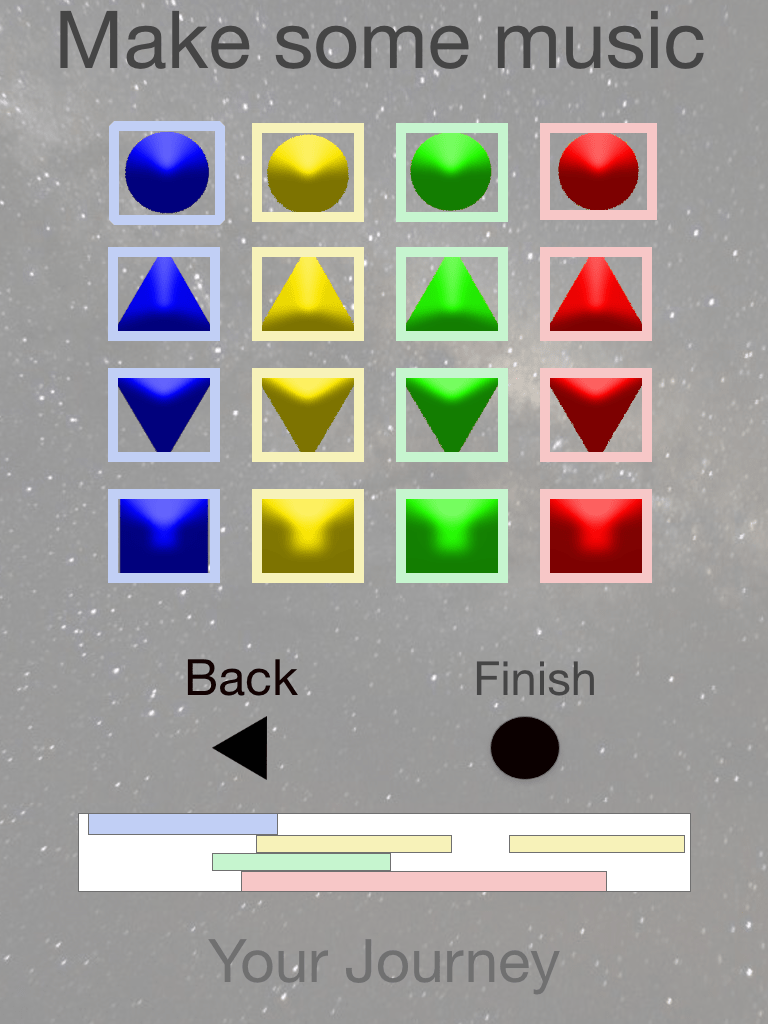

The creative aspects of my project can broadly be classified into design and composition; with the design aspect researching user interaction and design, specific design principles for children and the platform of HTML programming. The composition aspect focussed on the creation of a cohesive overall sound that allowed for the user to combine different emotions while introducing the user to contemporary and modern production aesthetic. The application platform enables several improvised, musically correct performances that follow four basic emotional behaviours.

As a musician and producer, I constantly explore music and technology within the audio production domain and this informed my approach to creating the interface and platform for creative performance. As an educator, I hope this tool can assist children with emotional wellbeing and also be used as a creative play device.

I utilised the services of an HTML programmer to help me create a web-based application. The musical elements are presented in a ‘loopable’ format and the user is able to launch and stop the different musical elements at any time. The emotion, on the other hand, is restricted to a single emotion per musical element. This approach allows the user to isolate a specific emotion, in the hope that they can create more complex emotional journeys through their interaction.

Research Component

My investigations were focussed largely on the role of music in emotional regulation, and then also music composition, UX/UI design and music psychology, in relation to creating a relevant and useful application. There are many fields of research that are beyond my expertise, but I have drawn on several experts in these fields to reinforce my purpose and research angle, these are discussed in the Literature Review section

The final output for this project is a fully functioning online app that can be interacted with remotely via an internet connection. The interactions are recorded and saved anonymously and I have analysed and extrapolated trends. I analyse this data in the Findings section.

Literature Review

“Music is an essential part of being human, with important status from the earliest stages of life. For example, singing is more effective than speech at holding an infant’s attention”

(Swaminathan, 2015)

The purpose of this document is to situate the development of this creative project within the relevant scholarly and practice-based literature. This document will outline the domains of knowledge that have contributed to this project so far and the methodology that I used to execute the design and delivery of the application.

This literature review is instrumental in my methodology and design. The mechanics and implementation of the application were informed by the body of literature, and the literature review has been organised into three sections; The first section represents the main domains of knowledge relevant to my research; music and emotion, musical cognition, design principles for children and mobile technology. I then discuss the Design principles and musical frameworks I have adapted for my project, and finally the challenges I face within my project.

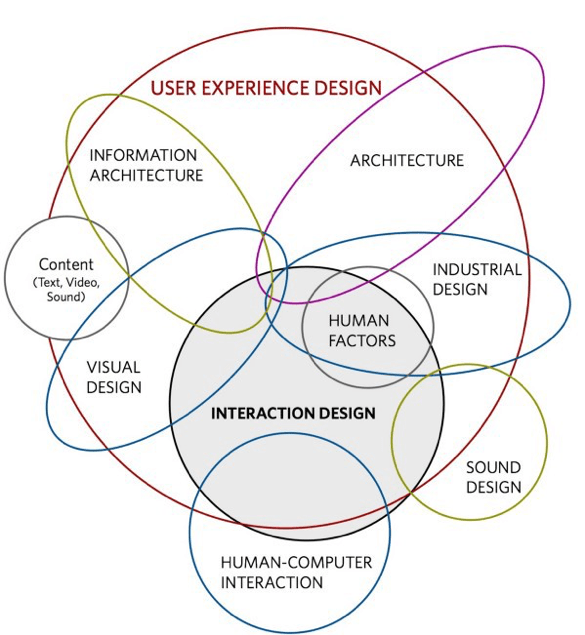

My project will focus on research and literature reviews from diverse disciplines including; music psychology, a subset of musicology and psychology (Davidson, DeNora, Egermann, Eerola, Grekow, Hallam, Swaminathan) framing the main research in regards to cognitive and emotional responses to music. I will also reference specific neurological research that supports the physiology of the human brain/mind (Levitin, Scheck and Berger) and how that relates to emotional response. After establishing the emotional connection with music, I will focus on the design framework; interaction and response to design aspects and functional elements also known as UX (User Experience) and UI (User Interaction) as it specifically relates to children. (Chiasson & Gutwin, Gelman, Goodwin, Kamaruzaman et al)

Music and emotion

Some researchers claim that music predates speech (Schneck & Berger, 2005), which would explain why music seems so hardwired within our physiological and neurological existence, while others identify the profound emotional effect music can have, it seems obvious for us to stop and ask, why music?

Music and affect

“The history of music in the human experience is at least as old as our civilised past and probably older”

(Schneck & Berger, 2005, p. 22)

It would be easily agreed that music and its emotional connection is entrenched in all cultural experiences and have several direct links to significant personal and cultural events. Within a western cultural perspective, we could look at the Greeks and the origin of the word music originating from the word muses. Recognising the impact and profound psychological effect invoked by music, “the Greeks believed achievement within the arts or sciences were divinely inspired.” (Schneck & Berger, 2005, P22). Interesting that etymologically, music is the only word that has maintained its identity from its original context.

In terms of the physiological effects of music, Schneck & Berger (2005) observes that music provides a means of communicating through syntax that the system understands and responds to profoundly. They continue to explain how music and the body share a unique symbiotic relationship independent of cognition. Music enters the listeners subconscious through indigenous and emotional pathways that require no further explanation, [music does not require any type of semantic interpretation] (Schneck & Berger, 2005, p. 30) nor linguistic familiarity. “Music communicates with the body by speaking the language of physiology” (Schneck & Berger, 2005, p. 24) and studies using physiological measures confirm that music listening is associated with emotional arousal. (Swaminathan, S., & Schellenberg, E. G. 2015).

It is rather obvious that music has and will continue to have quite a profound impact on us regardless of our cultural background or history. The emotional affect seems to be broader than just personal preference, and thus acts as a foundational element of my research and project.

Music and wellbeing

“…engagement in music (via listening and playing) has been found to have a positive role to play in everyday well-being”

(Davidson & Crause, 2018, p. 33).

Paul Farnsworth was a pioneering social psychologist and the first to explore music and behaviour in his text The Social Psychology of Music (Farnsworth 1958, 1969). It is worth noting how the discipline of psychology has been interested in music for over 60 years and even though the terms “well-being” and “health” were not a part of the discourse it correlates with social wellbeing (Davidson & Crause, 2018).

Wellbeing and creativity are a fundamental part of a balanced life for children, (MacDonald et al. 2002, Bunt. 2012) and this is where I see my project contributing to all children. Creating a fun, intuitive and simple means for children to explore music and mood, on a very accessible platform, with an underlying wellbeing application.

“Additionally, making music exerts considerable demands on the human central nervous system as it interactively engages memory and motor skills.”

(Davidson & Crause, 2018, p. 34).

Emotional cognition

Eric Clarke, Tia DeNora and Jonna Vuoskoski in their review Music, empathy and cultural understanding (2015) explore the capacity of music to promote empathy through a broad range of human sciences frameworks and setting cognitive empathy within several different neurological functions.

As humans are social creatures, we have an innate need to communicate feelings, share emotions and interact with our tribe. According to some Darwinian theorists, this is where music and dance could have started. “Music could be defined as a receptacle into which one’s feelings are placed in order that one may reveal one’s self to one’s self as well as to others” (Schneck, D. J., & Berger, D. S. 2005, p. 248). I see great value in this definition, that music is, in fact, a personal interaction for one’s self, where the feeling of euphoria and self-worth from the creative output, is the major driving force for humans to continue the cycle of evolution through creation.

Design principles for children

Sonia Chiasson and Carl Gutwin (2005) remind us that children have different goals, possess a wide range of skills and abilities and have been exposed to technology from an early age, so their needs and goals cannot be met by adult tools that have been scaled down to cater for children.

Designers need to focus on engaging these younger users through well thought out features and mechanics as value is only attained when their attention is maintained for longer durations. Generally speaking, for products aimed at “education or entertainment, user motivation and engagement are as important as task efficiency”

(Chiasson & Gutwin, 2005, p. 1).

As my application is focussed around multiple interaction experiences these frameworks have been vital for the creation of a successful and engaging application. Music is not enough to engage these users; ease of interaction and maintaining attention through excitement are things that I have observed as crucial for my focus group.

Children’s reading and writing levels could also vary significantly as age and stages of development differ and should be a primary consideration when designing and planning the interface. These abilities will dictate reasonable expectations in terms of interaction and needs and should be tested thoroughly during the prototyping stages of a project.

As a design framework (Chiasson & Gutwin, 2005) suggests a clear set of design principle based on cognitive, physical and social or emotional stages that will inform the interface design.

Several studies including Druin et al. SearchKids (2001), have shown that textbase interfaces are insufficient for conveying information to younger users and that much greater success was established using graphical interfaces. The use of graphically represented, content specific metaphors allowed children to navigate large information spaces with ease and accuracy. This will however only be valuable if the information presented is clear and age-appropriate.

Mobile technology

Developments in electronic assistive technologies now enable people with severe and complex disabilities to communicate and control their environment using alternative control interfaces…It has also changed services required of and provided by, health and social care professionals as they aim to optimise their clients’ independence through the latest technologies.

(Magee, W. 2006, p. 139)

With the 2017 Gallup World Poll data indicating that 93% of adults in high-income economies, and 79% in developing economies have mobile phones (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2018), positioning my application as a web-based program seemed like a logical and most accessible platform. This should allow for internet access via mobile service providers and would include “Cookies” that could allow for offline interaction without internet access. This will also allow for cross-platform / device access.

In the next section, I would like to discuss the frameworks and ideas I adapted within my project.

Music as a framework

Margaret Tan & Neha Khetrapal (2016) propose a specific framework that relies on a combination of music and images, resulting in emotional awareness instead of the traditional picture and text resulting in emotional recognition. This framework is in line with my project as I opted to use images and sound for the process of discovering emotional awareness.

During their research Tan & Khetrapal explore the biological and neurological healing and syncronising features of music (Tan & Khetrapal, 2016) and they explain how infants are, “from early on, confronted with the task of making sense of auditory stimuli that enters their cognitive system” (Tan & Khetrapal, 2016, p. 470). Initially distinguishing between speech and non-speech, followed by differentiating vowels vs consonants and finally word constructs. Parallel to this, emotions follow a developmental course that starts by interpreting emotions from music and tone (Tan & Khetrapal, 2016). All of this may imply that the [inference of emotion, at early stages, occur in a pre-linguistic manner where these emotions are devoid of language labels] (Tan & Khetrapal, 2016) but also worth noting that these may be culturally biased. Swathi Swaminathan and E. Glenn Schellenberg (2015) also add that before cultural-specific cues young children can use general acoustic cues for emotional musical judgements. Now it cannot be denied that this project is based in a western musical framework and that there is some sort of cultural bias, users from different cultural backgrounds may not experience the music in the way that the emotions are intended or represented, but I am hopeful a simple musical interaction could still provide a wellbeing experience and creative output.

Referring back to the physiological effects of music, Tan & Khetrapal (2016) observe that on a biological level, music possesses ‘healing’ features that assist the neurons in the brain to more effectively and synchronously communicate [Thaut, 2005]. It is a well-researched phenomenon that music has a neurological effect on the listener and that this could synchronise neurons and assist with learning (Schon & Tillmann, 2015).

Daniel Schneck & Dorita Berger (2005) go as far as to state that it is entirely feasible to propose that musical elements can communicate with the bodies genetic system, citing the secretion of opioids and the physiological effect that results from listening to your favourite music. Researchers have also found that studying choral performers pre and post-rehearsal indicated stimulated immune systems that are better able to fight off diseases. Therefore, it seems justifiable that one can use music to enable a state of wellbeing and emotional regulation.

In order to complete Tan & Khetrapal’s framework, I explored the picture exchange communication system (PECS) framework of (Charlop-Christy et al., 2002) and used emoji’s as the platform for my images; emojis could overcome linguistic challenges and are possibly more likely to engage younger children, the main target group for my application.

Tan & Khetrapal’s framework is a rehabilitative framework that incorporates music, their study is more focussed on autistic participants as they crave emotional experience and the authors feel music is the best way to do that as opposed to images that have been used traditionally. (Tan & Khetrapal, 2016) Part of my research is to build on this framework, and test whether music can assist school-aged children with an emotional recognition experience.

Musical element used to invoke emotions

Darwin speculated around pitch-specific vocal discharges that preceded language, possibly explaining why humans could be “pre-programmed to process music as symbolic communication of human emotional experiences.” (Scheck & Berger, 2005)

As the links between music and emotion have been discussed in detail, we need to now define music and how I have used it within my design framework. For this project, I am going to follow Schneck and Berger’s (2005) definition of music as “a specific combination of sound attributes, as embedded in what are traditionally considered to be the six elements of music: rhythm, melody, harmony, timbre, dynamics, and form.” (Schneck & Berger, 2005, p. 31)

In an attempt to simplify the framework, I will incorporate dynamics and form as overarching foundational attributes, leaving the focus on the remaining four elements creating a more focussed and manageable set of measurement tools.

Rhythm

Scheck & Berger (2005) establishes “rhythm” as a foundational element of music, the first element the human brain and body detects (possibly linking it to the natural rhythms we observe in our environment) and a physiological process that is ultimately capable of establishing purposeful activity (Scheck & Berger, 2005). Within my project, I had hoped that there would be a direct collation between the users’ emotional state of mind and the rhythmical element they will select to represent this.

The power of rhythm as a clinical intervention … it does not require any special training on the part of the participant. We noted that two of the three basic characteristics of rhythm, pulse and pace, immediately vibrate within the physiological system, causing entrainment that contributes to the systemic organization, consistency, rhythmic pacing and internalization, and various types of rehabilitation that result in adaptive responses. (Scheck & Berger, 2005, p. 158)

Melody

“In short, the melody gets right to the point; it immediately engages one’s basic emotional instincts.” (Scheck & Berger, 2005, p. 161).

Melody is easiest defined as that tune that gets stuck in your head for hours after hearing it for even just a brief moment; the elusive earworm that many musicians and producers’ pain over. Scheck (2005) states that melody is the element of music that makes immediate sense to the human instinct and intuition, where the “tune speaks louder than words”.

Harmony

Harmony, as a technique of “stacking notes” on top of each other, is used to enrich and create more depth or fullness to the emotional content and composition in general. These textures are unique depending on the relationship between the notes that are being played together, and one can manipulate the emotional intentions easily by just changing one note in a triad. There is no need for any formal musical training to perceive these changes, but rather there is some form of cultural harmonic entrainment that processes certain sounds more favourably and creates more pleasing sounds.

Harmony, as opposed to melody, is associated with several notes, each having a different fundamental frequency, superimposed on one another, vertically, to create a chord (as opposed to linked together horizontally to create a melody) (Scheck & Berger, 2005, p. 191).

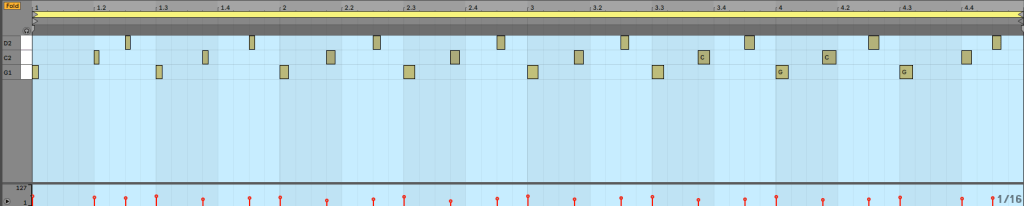

Technically harmony was not used as a stand-alone element, harmony was embedded with the melodic elements and I instead used Bass which would normally form part of the rhythm.

Timbre

Timbre can most simply be illustrated in the fact that two completely different instruments are able to play the same musical note, or perhaps more technically defined according to the ASA (American Standards Association), as the quality that makes sounds of the equal pitch and loudness different. Timbre is what makes us realise that the note is being played on a piano and not a flute.

Timbre in the context of my project was the main compositional framework, I used the aesthetic differences to create a representation of emotions. I created all the musical compositions in the same musical key (C Major and it’s relative A Minor scale) intending to explore how Timbre can be used to create emotional context.

This richness, fullness, and depth is referred to as sonority, which is to the element of harmony what timbre is to the element of pitch. (Scheck & Berger, 2005, p. 191)

In the case of timbre, the sound frequencies are enveloped within the frequency spectrum surrounding a single fundamental tone. In the case of harmony, the sound frequencies are enveloped within chords comprised of three or more pitches sounded simultaneous (or in a variety of flowing accompaniment styles), each pitch contributing its own timbre, as well. (Scheck & Berger, 2005, p. 191)

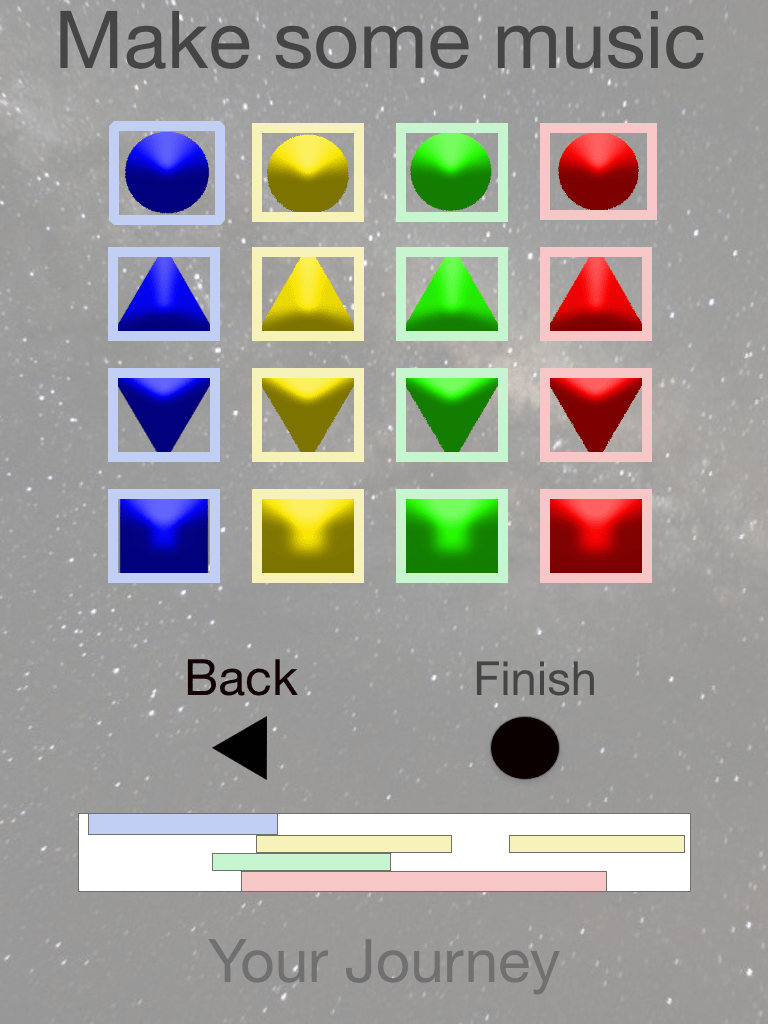

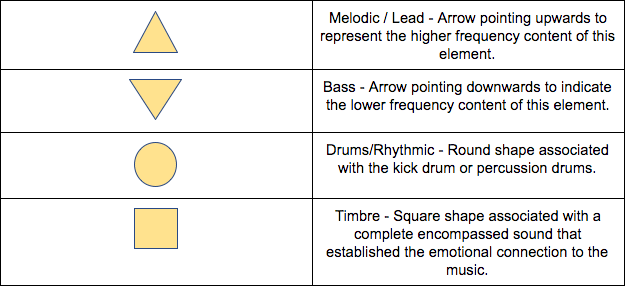

The decision to use these elements as the main interactive musical components is two-fold, one to simplify the musical content into more familiar groups and secondly to create a visually pleasing and design-centric interface.

Design Principles

Within Chiasson “Stages of Development framework”; I have identified a specific group of subsections that I will be focussing on as the design guidelines for my interface:

Feedback and guidance

Children expect immediate feedback and/or results from any interactions with technology – I have witnessed how quickly they get frustrated if nothing happens after the first click or swipe. They also need to be able to navigate and understand the workflows without much learning. The interaction needs to be as intuitive as possible or clearly guide the user through feedback while considering the abilities and expectations of these younger users.

On-screen icons need to represent familiar items and be intuitive for children. For example, use a stop sign for stopping activities and make buttons have a 3-D appearance so they appear clickable. Visual or audio feedback should be present when children move their mouse over clickable portions of the screen to indicate what is clickable and what is not. For audio feedback, it is desirable to have a short delay so that children can deliberately activate it; otherwise, they tend to hear random audio because their cursor has already moved somewhere else (Chiasson & Gutwin, 2005, p. 3)

Imagination

Children sometimes tend to immerse themselves in their environment through their imaginations. Sometimes this could cause them to be unable to distinguish between the real world and the interaction, leading to them getting distracted from the task. Although this could be great user experience, maintaining the user’s attention and interaction will be important for educational based applications.

Care should be taken when using metaphors for interfaces as children readily immerse themselves in the environment. While this leads to more intuitive interactions; it may also lead to expectations that exceed the bounds of the interface. (Chiasson & Gutwin, 2005, p. 4)

Mental development

As mentioned before, younger users may have difficulty with abstract concepts, and as Druin et al.’s work with “SearchKids” (2001) highlights, children process and organise information in different ways depending on their stage of development. They also do not possess the in-depth knowledge to be able to navigate complex interfaces, which brings us back to the use of graphical interfaces and image lead navigation systems.

Physical development – Motor skills

Tasks like drag and drop or mouse clicking for extended periods may be difficult depending on the level of motor skills the users have; it is, therefore, crucial to consider this when designing for age-specific or non-typical users. These features can lead to more engagement as users are more motivated by the ease of the functionality.

Challenges

Beyond the general challenge of defining emotions and responses to music, a more specific challenge we face regarding the musical and emotional response is a phenomenon known as the Contrast Effect; Schellenberg notes that the emotional context of music is evaluated and will be influenced or fluctuate depending on the accompanying music (Schellenberg et al., 2012). Another factor that adds to the complexity of this subject is Contrastive Valence; [a mismatch of musical prediction and outcome. If a positive event is expected, a negative outcome can be overly unpleasant.]

Additionally, research shows that a person in a sad state of mind prefers sad music over happy music as they can relate to the aesthetic that matches their mood (Schellenberg et al., 2012).

It has also been observed that [emotional responses to art differ from responses to other stimuli because they occur on two levels; one related to the emotion expressed by the work of art, the other to the perceiver’s evaluation] (Bhatara, A. et al., 2010, p. 42) It is almost impossible to determine how any art form will be received, as every person will have a very personal experience when interacting with art.

All these challenges are noted as informative and I have attempted to mitigate their impacts by considering them during the design phase and creating a measurement where the user reflects on the change (if any) of their emotional state prior to the interaction, which will identify a consequence or result after the interaction rather than attempting to identify an emotional state.

I am aware that there are very close links between my research within this project to music therapy, but for reasons of disciplinarily and a lack of personal qualifications this project will not be viewed as a clinical therapy tool.

My Project

When I started planning this project and the research I knew that I wanted to approach my research topic from an interactive foundation with music as the main vessel for wellbeing. My project differs from all other tools and applications I have found as it allows for interaction and complete freedom to express several different musical topics while measuring the effect of the interaction. I believe that ultimately this app should be further developed to become a stronger measurement tool for clinical practitioners as well as expanding on the user experience through continuous improvement and revision.

Design and Process

Any project needs a well-planned journey and design thinking was going to be my map, UX as my strategy and design principles as my framework.

Design thinking

Empathy

The first step in the process of design thinking is empathy; this is achieved through the development of a personal and deep understanding of your target market and particularly how your product/service can assist and enhance their lives. Traditionally this is done through a process called a ‘persona chart’, which follows a process where you enter the psyche of the target market, allowing better insight into their personality, actions and behaviours.

Personas are archetypes that describe the various goals and observed behaviour patterns among your potential users or customers.

(Goodwin, 2011, p. 229)

As I have had some experience working with teenagers (and my everyday life with my stepdaughters), I have been able to identify behaviours, challenges and emotional journeys. This includes observing interactions with technology which helped with my planning phase. I was also able to get direct feedback from my students that I mentor by asking specific questions and showing them other musical applications.

Define

Defining my problem was the next step and was useful to ensure I had a clear scope, purpose and aim for the project. When I developed my research question, I broadly defined the purpose of my project as:

Design and develop an interactive music creation application that could serve as a wellbeing tool and assist with emotional recognition.

(Dreyer, 2019)

As mentioned previously I opted to stay with a wellbeing approach as to not enter into the scientific realms of clinical practitioners and psychology, leaving the main purpose of the application to focus on creative expression, fun and wellness.

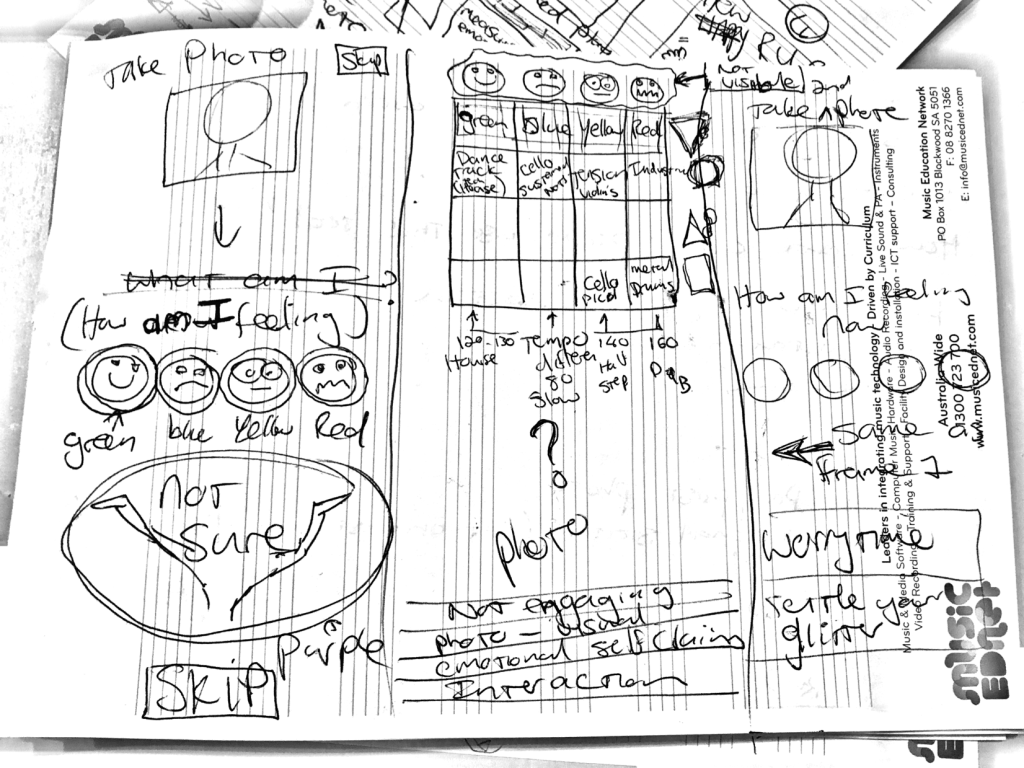

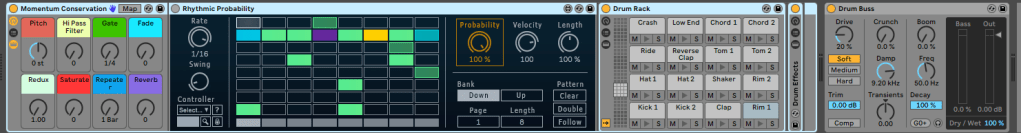

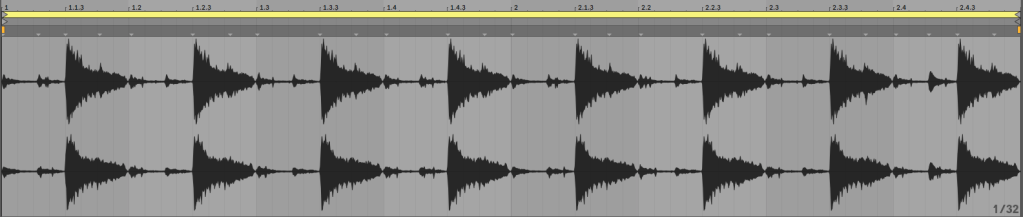

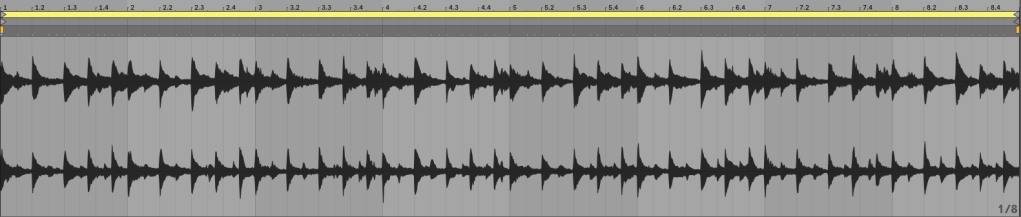

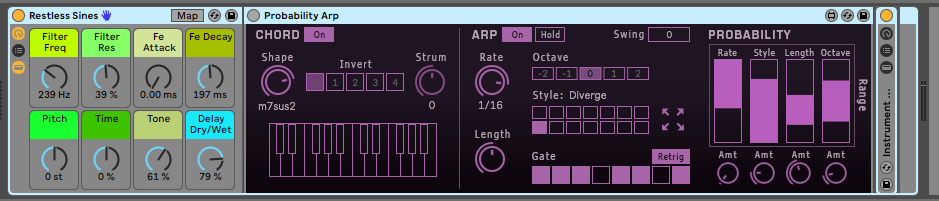

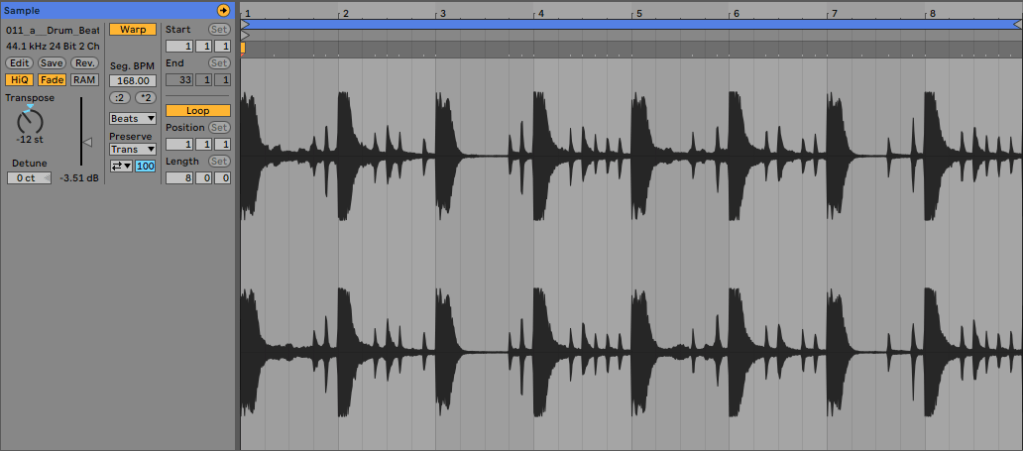

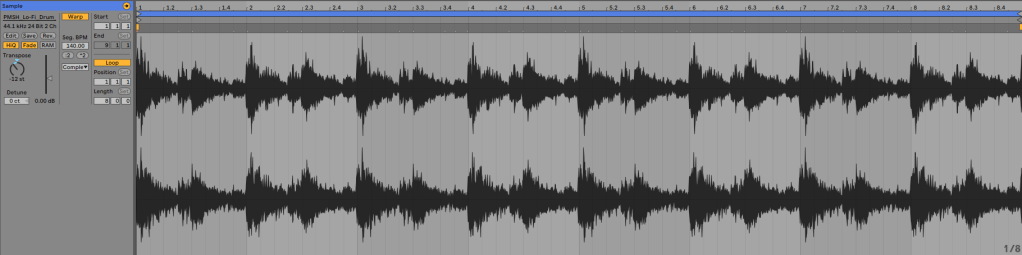

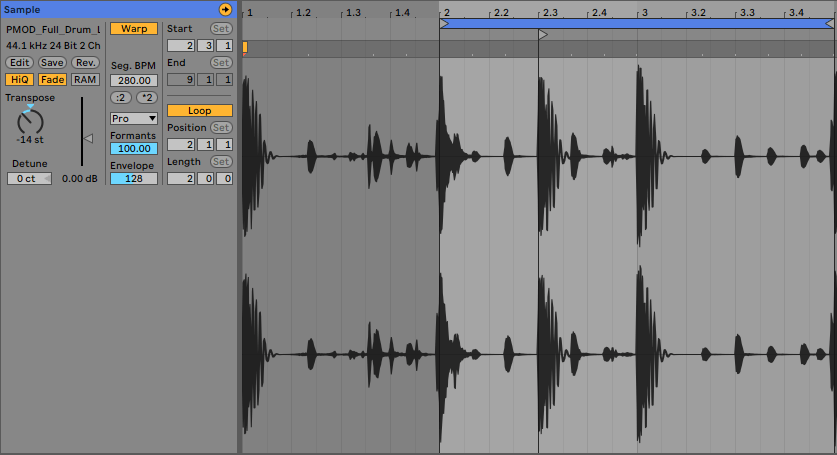

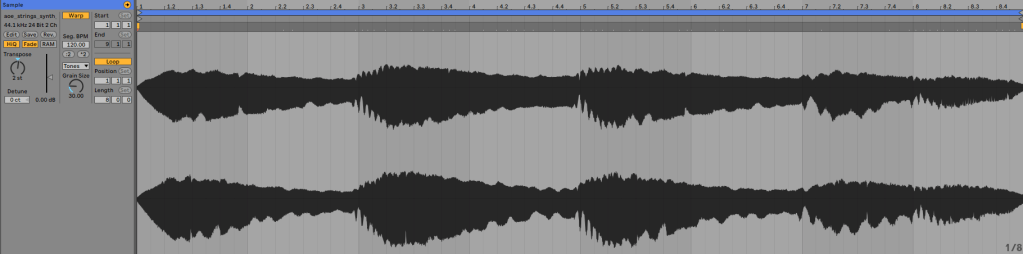

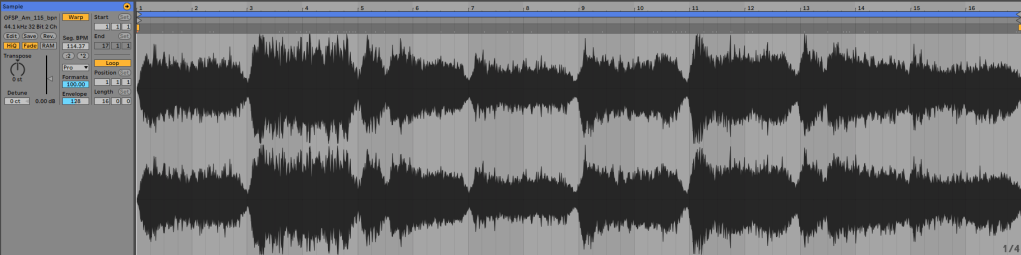

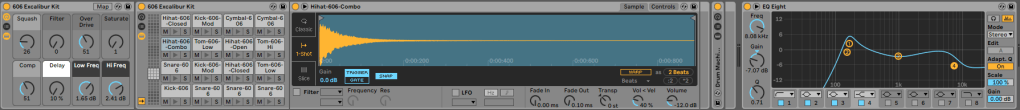

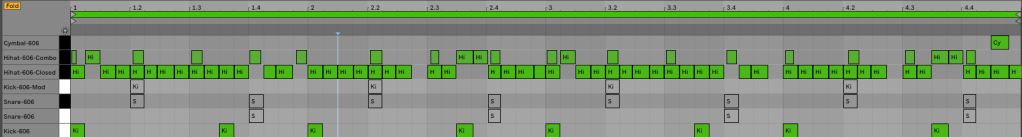

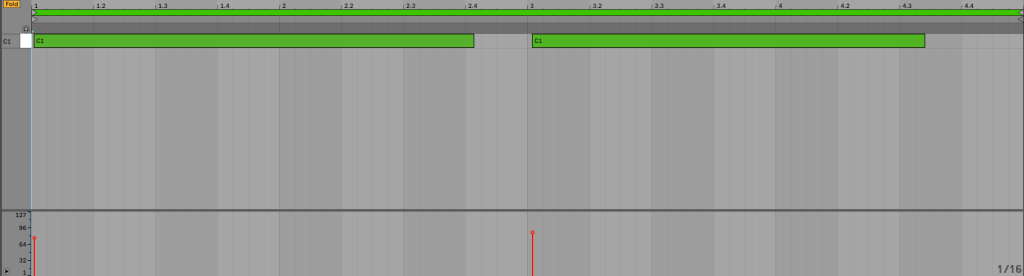

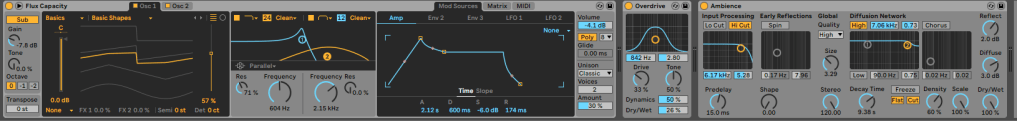

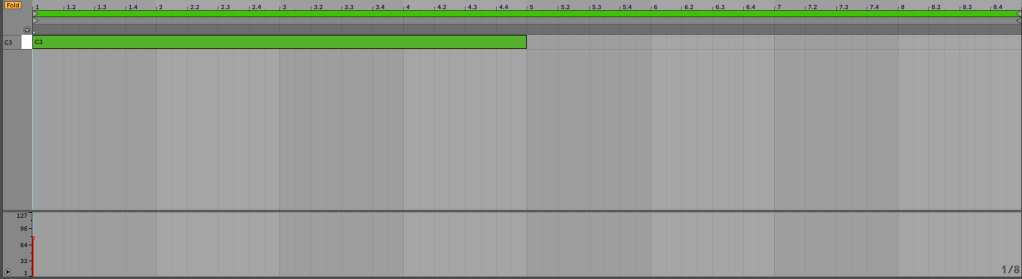

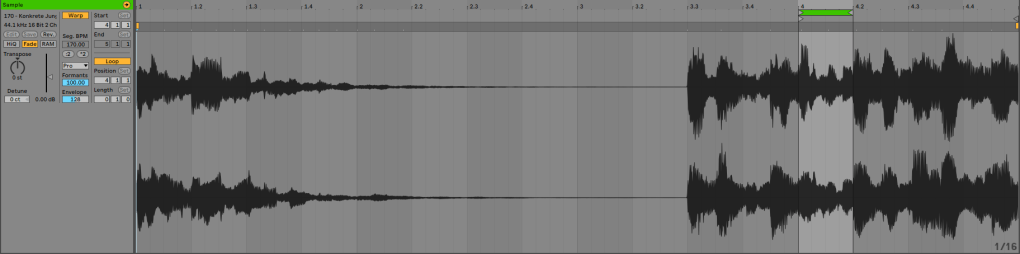

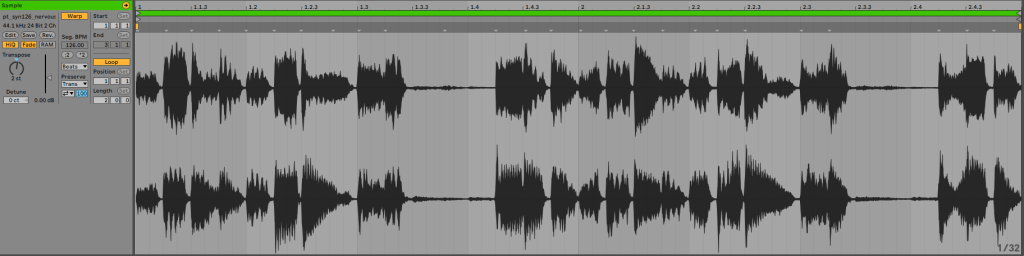

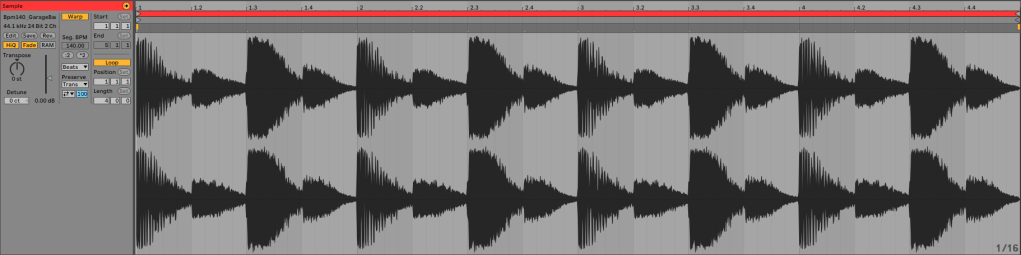

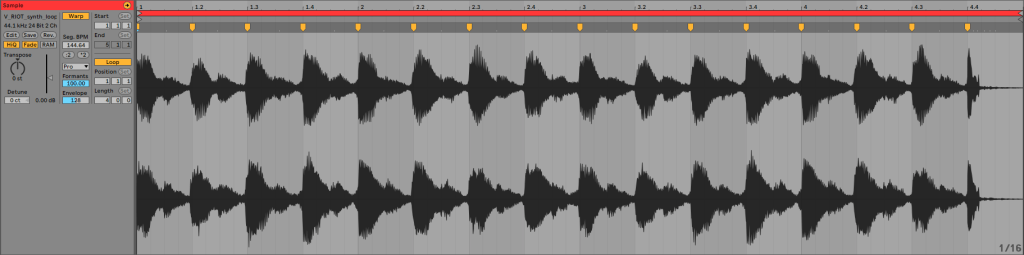

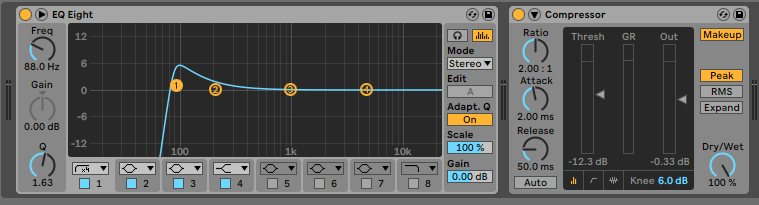

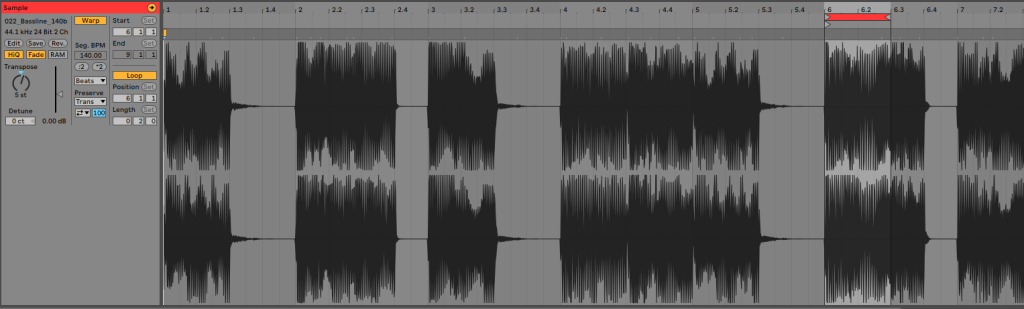

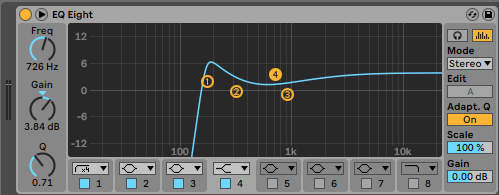

Design elements of this project are very important to ensure great UX/UI interaction. I had been refining this process through researching existing applications, reaching out to peers and finally interacting with target group candidates, all the while informing changes in my approaches and design prior to prototyping. A practical example of this was setting up an Ableton session with simple musical loops to investigate how children interacted with the concept. (See Appendix)

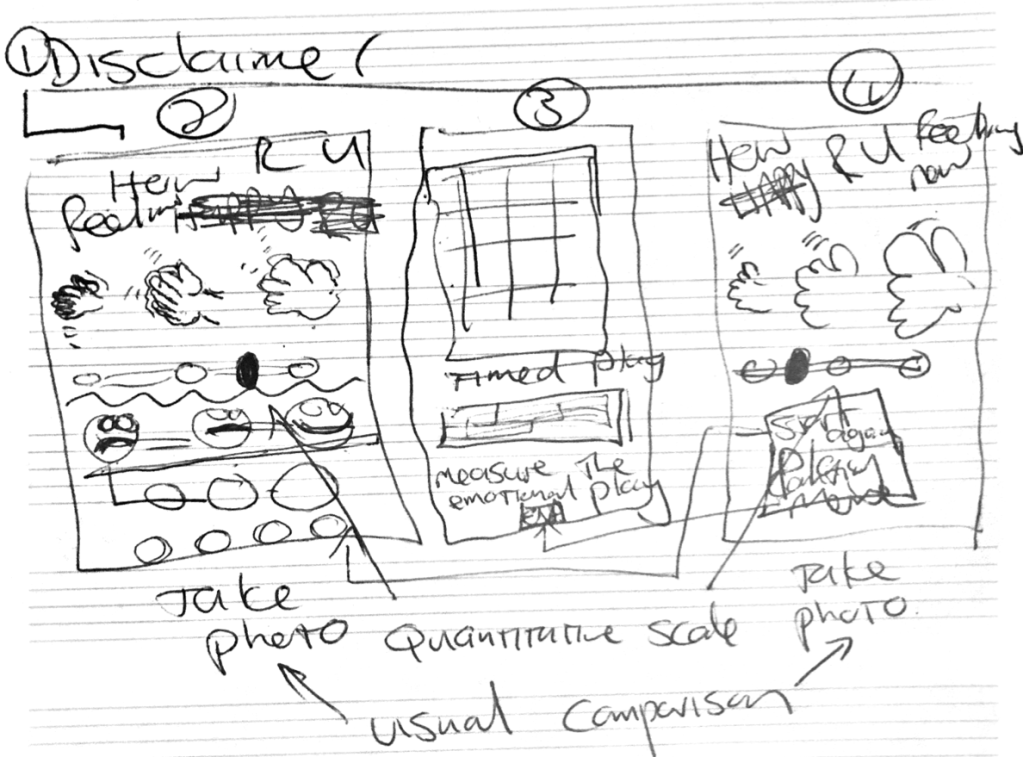

One of the programs I researched was “Settle your Glitter” (Fig. 3), a great example of a wellbeing app that utilised the same measurement of emotions pre and post the main experience. I analysed the user interactions and flow and noted what actions were intuitive and what seemed unclear. For example, I couldn’t get the glitter to move on my device even though I knew it was supposed to do that. This illustrated the value in ensuring your application is tested over several different platforms with different operating systems.

Ideation: Solutions / Design

As with most creative processes this project had several ideation steps, settling on a focussed and simplified approach for the final product. For the application, I moved from a MAX MSP based program to a web-based application while the music had 3 major revisions to transpire into this final version.

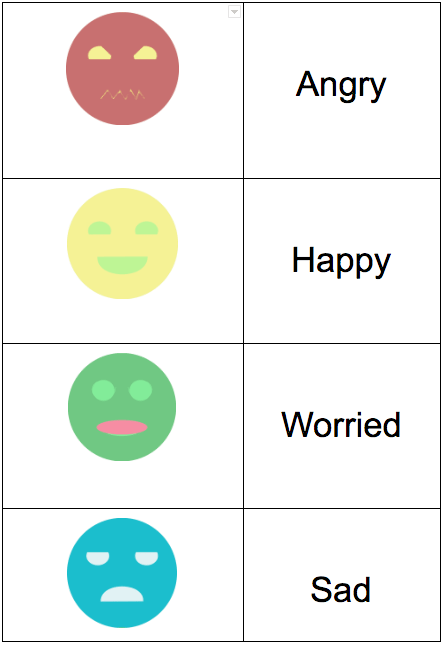

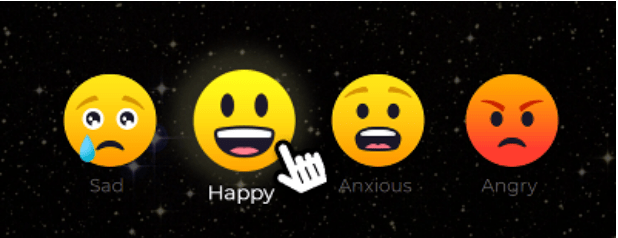

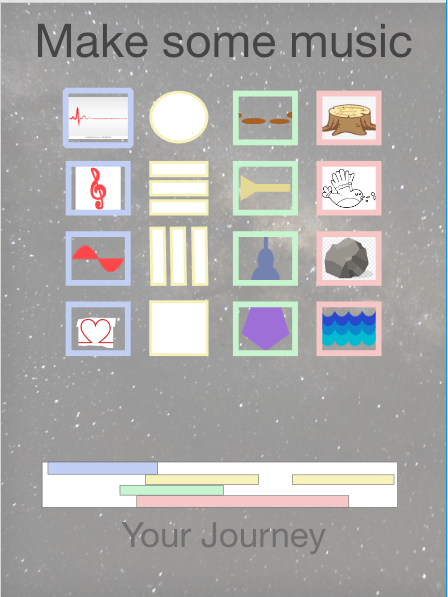

The application functionality is organised into 4 basic human emotions (Happy, Sad, Worried, Angry) with 4 different musical elements (Drums, Lead, Bass, Timbre). I chose those basic emotions as several studies have indicated the folding down of the traditional 6 emotional states (which also included fear and surprise) into these 4 states. The participant interacts with these elements and possibly establishes or recognises an emotional state or “mood”, having access to simultaneous emotions will allow for the representation of more complex emotions, perhaps illustrating jealousy as a combination of “worried” and “anger”.

I revised the term “Worried” from “Nervous”, as agreed by my supervisor, this may be slightly confusing for younger children.

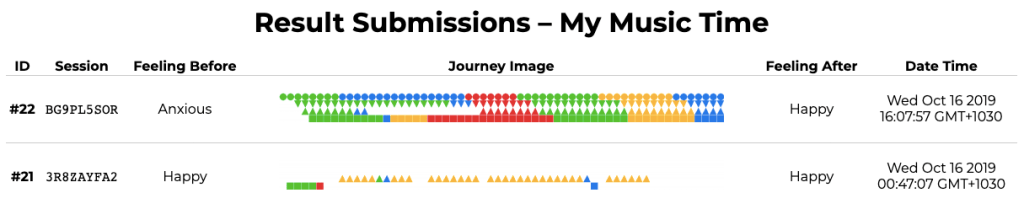

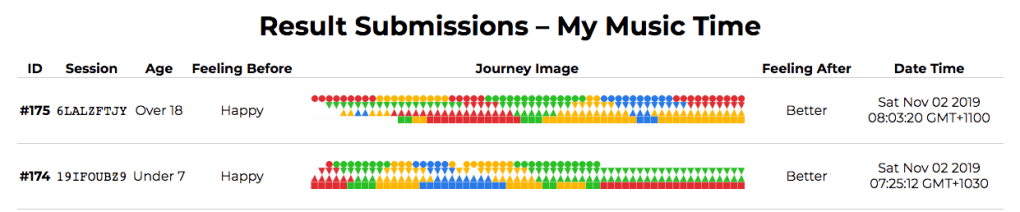

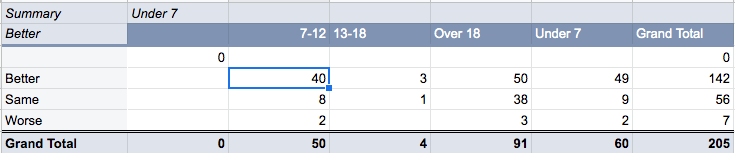

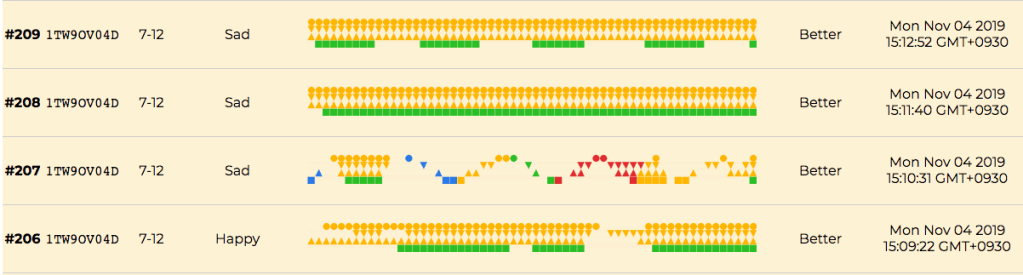

Being able to record the interaction through the web application and capture a visual representation on the admin page, (See Fig. 4) I was able to analyse the emotional journey of the participants and established patterns. It was after the first week of testing the application and consultation with my supervisor that we established a more useful reflection for users would ask whether they felt: “better”, “worse” or “the same” instead of the same emotions introduced at the start of the interaction. We also added a questionnaire to establish the age of participants that will assist with the interpretation of data.

I was interested to see how emotional states are affected after interacting with the program, and particularly how many interactions the average user would engage in.

(Copyright J Dreyer, 2019.)

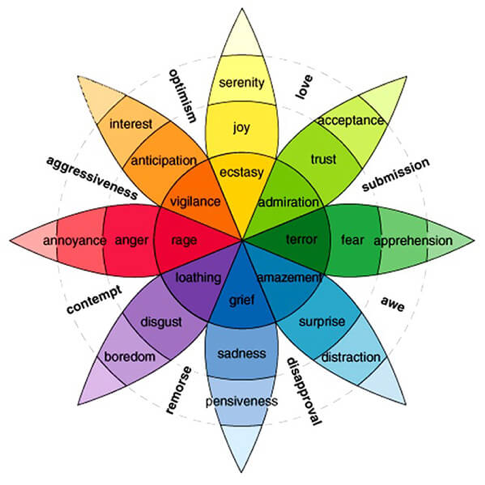

When designing the User interface, and assigning colours associated with emotions, I used Robert Plutchik’s Emotional Colour wheel (FIG 3). I have also observed other therapists and clinical professionals use the same colours for worksheets and monitoring activities with special needs children.

Design strategies

Interaction Design

Simply put IxD is the interpretation and orchestration of users’ interaction with your product and in my instance, this will be aimed as a wellbeing application and how children will interact with the music creation elements.

My design strategy relied heavily on a combination of prototyping/testing and focus on design principles for children.

Prototyping

Ward et al. (1995) describe the practice of building large numbers of prototypes to explore design alternatives before selecting a final design. This is contrary to common design wisdom that calls for deep exploration in the conceptual stage, before fabrication

(Yang, 2005, p. 649).

My approach was simplified as I already possess a lot of experience and a deep understanding of music technology and performance-based applications, my personal experience/observations with my target group also guided the production and compositional prototyping.

There were several iterative design cycles with refinement and updates, for the design, user experience and user interaction, as my process unfolded, my understanding expanded and my knowledge deepened.

Prototypes can be thought of in terms of their purpose, or the categories of questions they answer about a design. Ullman (2003) describes four classes of prototypes based on their function and stage in product development:

- To better understand what approach to take in designing a product, a proof-of-concept prototype is used in the initial stages of design.

- Later, a proof-of-product prototype clarifies a design’s physical embodiment and production feasibility.

- A proof-of-process prototype shows that the production methods and materials can successfully result in the desired product.

- Finally, a proof-of-production prototype demonstrates that the complete manufacturing process is effective. (Yang, 2005, p. 651).

I followed the first two steps outlined by Yang using Adobe XD. This design tool is specifically designed as an application prototyping software and allows for rapid visual and navigational prototypes used for testing.

Initially, I also used Marvel for mock-ups but found XD far superior in terms of the ability to actually test navigation and menu structures as well as being able to export assets to developers with greater ease.

It was during these early stages and sharing with the developer that we refined a few elements, including the positions of the arrows as to not confuse the user with UP/DOWN functionality. (See Fig. 5)

After more testing I have identified a few other design alterations that may benefit future versions of the application, this includes an untimed interaction with a manual finish button, even though this was initially in the design I decided to rather go with a timed interaction to encourage users to return to the interaction and use that as a measurement tool.

Framework for children’s design

When designing for Children, I utilised two approaches; the first being a design-based approach by Debra Gelman in her Design For Kids: Digital Products for Playing and Learning book and the second an ethics-based approach as outlined by the Designing for Children Organisation, http://designingforchildrensrights.org/

For the interaction-based design, I focused on Gelman and her framework for digital design that introduces us to her four “A’s” (Gelman, 2014)

Absorb, Analyse, Architect, Assess.

(Gelman, 2014)

These steps are similar to the design process for adult products, but the way one evaluates programs for children, the elements one looks for and the way one measures success will be different (Gelman, 2014).

I have found this framework to be useful and appropriate for my design thinking process as illustrated earlier in the Methodology section as well as the Literature review.

Absorb

“Kids lack the deductive reason that adults have and as a result, they cannot make the cognitive leap between an intangible idea and an actual interface” (Gelman, 2014, p. 17).

To really understand your target audience and be able to design the best user experience, you have to observe and understand the users. In our case, these will be digital natives who think and interact completely differently than some adults do, some of these users are still familiarising themselves with user interaction and technology flow.

Analyse

Once observed, the information was analysed and grouped to establish broad trends, challenges and possible “flows”. Gelman suggests the “Affinity Diagramming” process to help understand children’s actions, assumptions and ideas. It is very important to find the sweet spot for your app so you can create a baseline for interpretation, then “you will be able to interpret the themes and actions based on this cognitive stage“ (Gelman, 2014, p. 19).

Architect

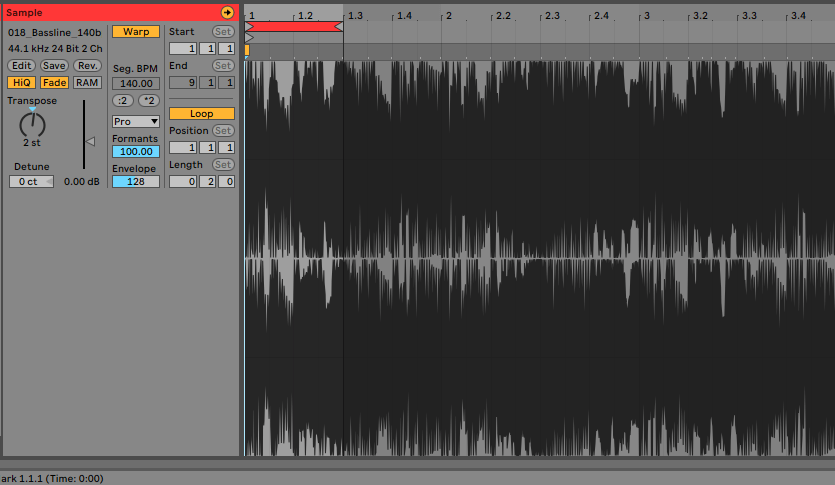

At this stage, we start creating the structure and function of the system. Gelman suggests a participatory design activity where she normally lets the focus group design and interact with the basic design idea. I have done a similar step in early prototyping and research by creating a session within Ableton where I asked some kids to trigger sounds. The point of my exercise was to establish the conceptual understanding of triggering sounds and loops and I gained some valuable lessons from those early observations. This exercise lines up well with Gelman’s suggestion to create some form of workable prototype to see how flows and interaction are experienced.

Assess

“like with adults, what kids say they want, what they actually want and what they think they want, are often quite different”

(Gelman, 2014, p. 24).

Designing products for all users require a process of iterative assessment and testing, and when designing for children special attention is required as the feedback from prototyping may be more ambiguous and require interpretation.

Ethics

The Designing for Children Organisation set out to “create awareness about the importance of keeping children’s rights in mind when building products and services.”(What We Do. 2018) and these ethics are very important factors I considered during my design, development and testing phases.

One of the main issues was Data collection (Key Principle 5) and as I relied on collecting some sort of Quantitative data for my research I had to ensure no one’s personal details were captured. With the help of my developer, we were able to assign a unique session ID to every user that started the application. This session ID would remain the same until a user cleared their cookies. One of the challenges with this approach is that if there were several users using the application on the same computer I would not be able to distinguish between them. With the introduction of the “age identifying” page, we could limit this skewing of data as long as users were not the same age. But there was still a very great likelihood that some users may use the same session ID.

Key Principle 1 states: Everyone can use; One of the main reasons to establish this program as a web-based free program was to make it as assessable as possible. Future iteration may include an offline function.

I stayed within the Key Principle guidelines and aimed to make the program unintrusive, fun and as intuitive as possible for the users. The Users were encouraged by their parents to play and there was no reward for participating.

Research within design thinking

In addition to my overall project research and literature review I also conducted some specific, hands-on UX/UI research:

This included researching basic design principles and the platforms or programs I was going to utilise in my prototyping stage, researching applications that are already in the market place and finally observing participants using not only music or wellness applications but workflows and interaction with applications in general.

From what I had observed, one of the greatest challenges is to create an intuitive and engaging application, that neither frustrates nor bores the user. I feel that I achieve this with a simplistic and minimalist design approach combined with the use of Emojis and I will elaborate on the creative process next.

Creative Process

There were two main creative elements to this project; the design of the application and the musical composition.

Design

In the Children’s Design Guide, Key Principles (version 1.3)point 3 states:

“Help me understand my place and value in the world. I need space to build and express a stronger sense of self. You can help me do this by involving me as a contributor (not just a consumer). I want to have experiences that are meaningful to me.” (Children’s design guide n.d., point. 3)

Involving the user to pursue self-expression and creative play was one of the main goals I pursued, and I based my design on these principles.

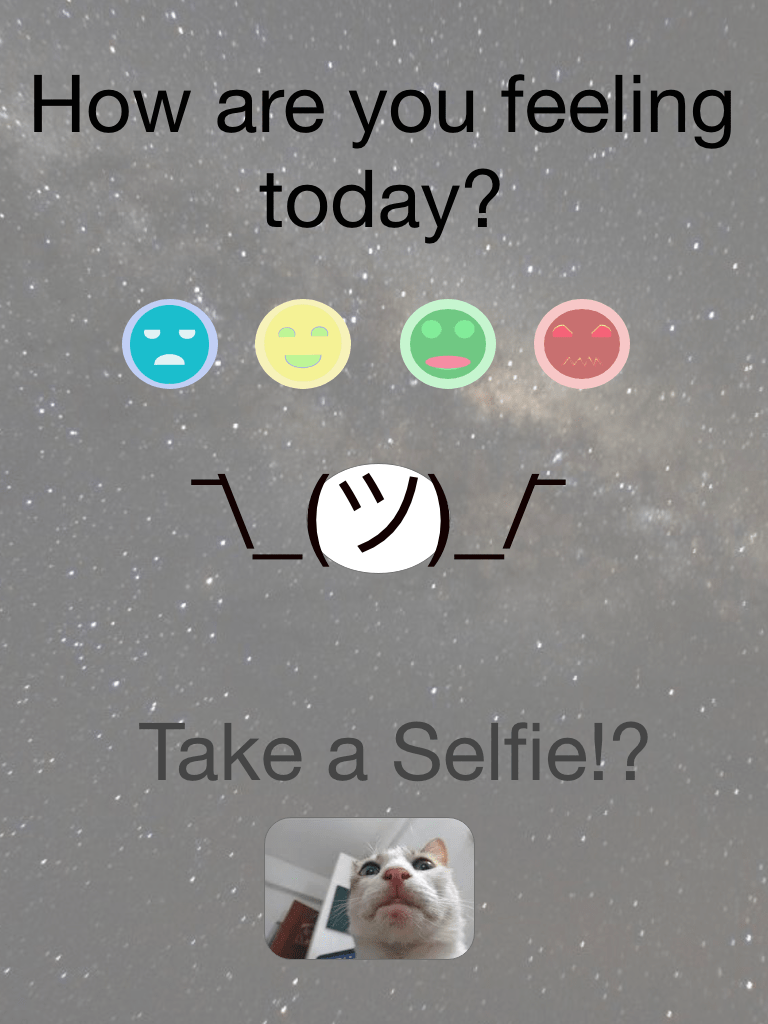

The main interaction of the application is split into three stages. First, the user establishes how they are feeling, after which they interact with the music-making platform and finally, they reflect on their emotional state and whether there was any change in mood.

As I have mentioned prior, I did look at other similar applications and this informed by decisions about how to design my own application.

Initial ideas included sliding scales to establish the emotional states as well as the use of selfies to supply more data for analysis, but I quickly realised that simplicity is key, and if I were to follow the ‘Designing for children Ethos’ I needed to rework this design.

Working with Colours:

As mentioned in the methodology, the use of primary colours to establish a link with emotional states is a common practice among clinical workers and I adopted and interpreted this framework. As there are no definitive rules, I did apply some creative freedom and interpretation in my colour assignments; an example of this is the colour green, which is often used as “jealous”, but I used it for my “worried” emotional state.

A great contemporary example of these emotion and colour association can be seen in the animated movie, Inside-Out.

Working with Faces:

As part of the user experience, I wanted to explore a way to engage the users to explore the interface and use their imaginations. Using emoji’s was one of the first ideas that came to mind.

As part of the design process, I did design my own versions but after some reflection, I opted to use the standard emoji’s as I felt these would be better recognised and understood.

As can be seen in Fig 14. the first iteration from the developers has the standard emoji colours. I felt that it would benefit the users to have the emojis the same colour as the musical blocks to assist with the association that the music is in fact aligned with emotion and colour.

Working with Shapes:

For the musical interaction page, I also worked on the concept of association and interpretation, so I needed to find a way to represent the four musical elements.

From early on I thought the idea of using shapes would be a more interesting and engaging approach, instead of using graphic type images. Again, interpretation is a very personal experience and what I consider to be logical or self-explanatory may not be the same for anyone else. This was clearly illustrated when I discussed these initial ideas with my supervisors and one of them mentioned that the heart image should be associated with the drum beat and not the timbre as I had suggested.

I used my creative prerogative and opted with the following associations and images, with the aim that the user would be interested to explore the different shapes and work out what they do.

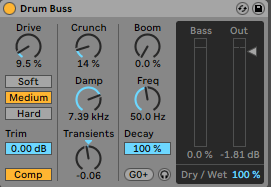

Music

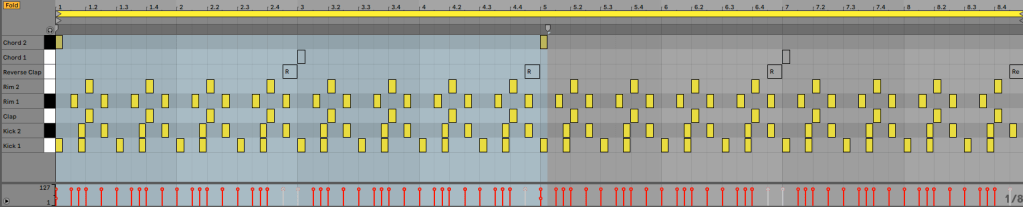

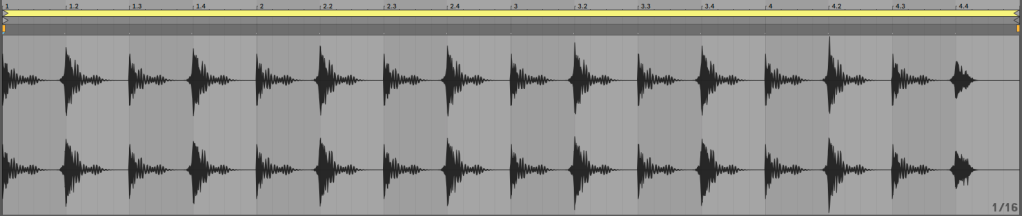

One of the philosophical issues, as noted in the Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology, is that “music itself can neither be happy nor sad” (Grahn, 2016, p. 285), but that we have been programmed within our cultural context that certain sounds, musical scales and chords, are associated with said emotions. During my research and creative process, for the musical elements, I quickly came to the conclusion that I needed to not focus on a traditional musical scale angle to represent certain emotional contexts. It is so well known how Major scales represent happy sounds and Minor scales sad sounds, but as mentioned before within this simplicity there are several issues including the Contrast Effect that could influence a users reaction or interpretation. So I decided to rather focus on timbre and employ sound design techniques to create the music. All music remained in the scale of C Major and I employed other compositional techniques to help me establish these emotional connections.

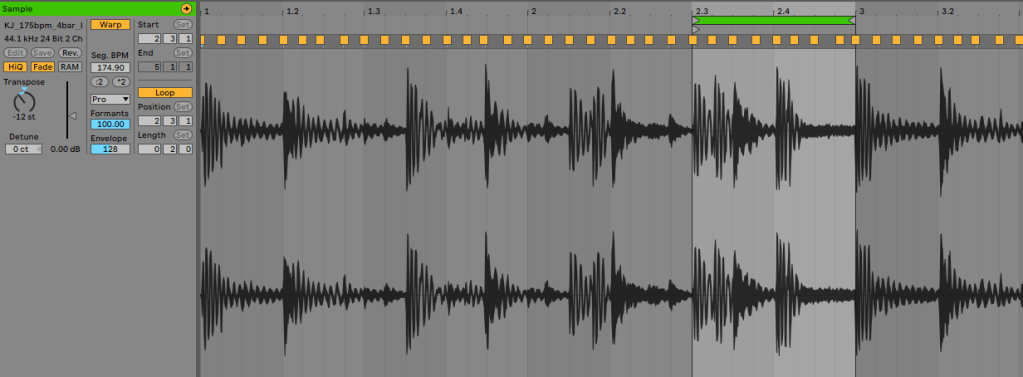

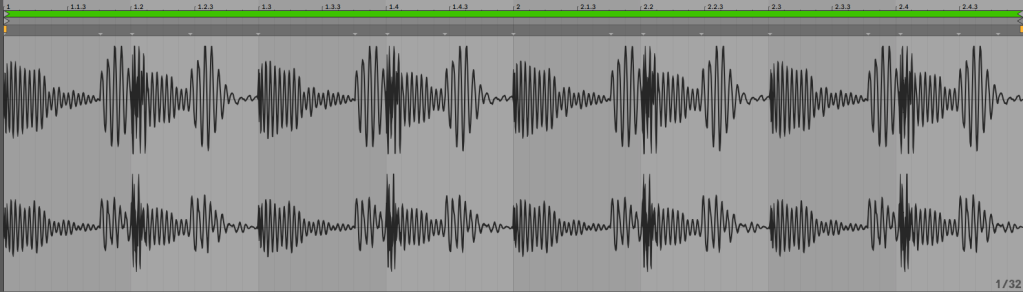

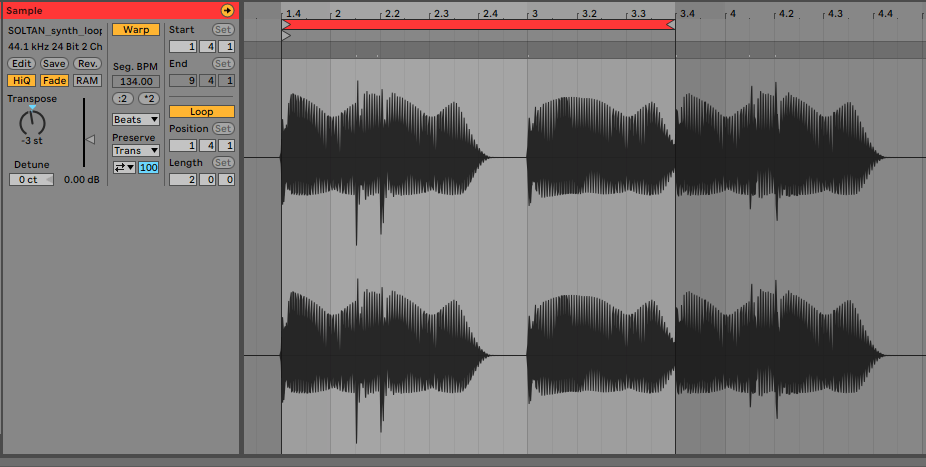

I experimented with the length of the music loops and found that eight bars is the optimal length to ensure that the phrases from different emotional pieces are best able to work together, and as we were in the same musical scale, all the musical pieces should work together and allow for different combinations from different emotional sets.

Initial musical ideas:

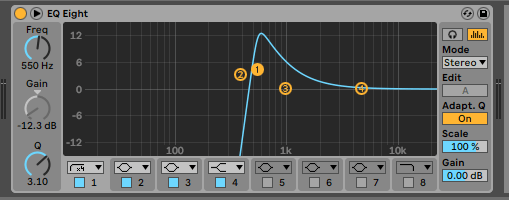

My first iteration was based on the principle that I will use the same instruments for each emotion and only through signal processing will I be able to create the differentiating timbre required. This created quite a challenge and the music wasn’t very exciting. I quickly realised that I would need to draw from different pallets of sound. (See Appendix for examples.)

Even though I used some reference tracks, ultimately I have used my artistic discretion to create pieces of music that would represent the emotions in a way that fit my creative practice. In the following section, I will give some examples and illustrate the sonic qualities that I used to create my pieces.

Details of the final instruments (incl. Effects racks) and Midi composition techniques can be found in the Appendix.

Happy

Traditionally within Western culture, happy music is represented with a Major musical scale and Major chord progressions. The tempo is also normally quite upbeat (120 – 130 Bpm) as can been seen with dance music. Chicago house music is a great example of “happy” sounding contemporary dance music; historically the genre was formed from disco music in a cultural and socioeconomic environment where diversity and gay culture was celebrated. The genre also employes positive vocal sampling that often imitates a church sermon, or themes of love.

In conjunction with a “house” framework, I drew inspiration from a “tropical” aesthetic sound pallet when I created the music for the “happy” emotion. I thought that the association with a warm beach summer and perhaps a reminder of holiday would invoke a happy emotional connection.

The use of bouncy sounds and higher-pitched plucked percussive sounds is one of the main production elements in this piece. Using live percussion and claps in the rhythmic section also creates more of a human connection that seems to invoke a happier/livelier feeling. This emotion was sighted as the most “well-liked” musical element and received quite a few compliments on the “good vibes” and “happiness” people experienced.

Sad

Minor chords and scales are considered “sad” in contrast to the way that Major scales are “happy” within a western musical construct. The rhythmic elements are also traditionally slower, perhaps 80 -90bpm, and would often imitate a type of contemplative march or ceremony.

Chopin’s Sonata Op. 35 Mvt. 3 (Funeral March) could be considered the pinnacle of a sad sounding song and possesses the grimmest associations.

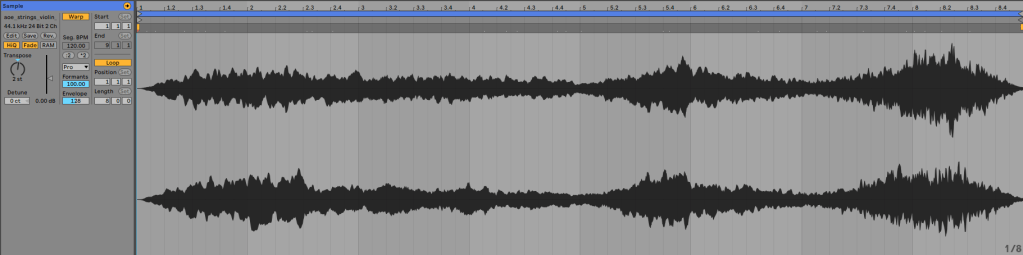

To create the sad aesthetic I focussed on a slower pace and more drawn out and slow-moving instrumentation. I used classical stringed instruments as I felt that their sonic characters could easily invoke this emotional connection. I also incorporated more contemporary synthesised sound to create an eerie and lonely ambience. The rhythmic elements were purposefully programmed very sparse and minimal with a marching style snare drum to simulate a funeral type march.

Worried

Building tension is a fundamental part of Western music composition, and there is a myriad of great examples in classical music (Chopin – Nocturne op.9 No.2, or perhaps Mozart’s Requiem). This tension is always created by using dissonant chord structures and unresolved progressions. In a more modern context, a lot of Jazz music uses diminished chord structures with fast-moving patterns to create really intense musical experiences.

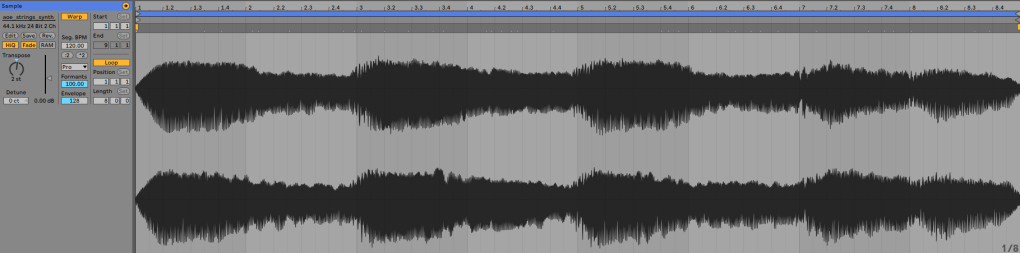

There is a level of intensity that is created with the use of Staccato violins and a seemingly “broken” drumbeat in the Radiohead track Burn the Witch, and this is exactly what I attempted to do with my “worried” piece. I focussed on a very sparse drum element and tried to have the stringed instruments lead the arrangement. Traditionally Yorke (Radiohead) also experiments with some really interesting musical chord structures and these tension-building moments can be felt during the crescendos. I, however, did not employ any diminished chord structures as mentioned earlier but instead focussed on the A minor scale (Relative of C Major) and sound design techniques.

One of the production techniques I used was a sustained high pitch sound with a modulating filter envelope that helps to create tension, this is a standard procedure and can be seen in many classical and modern compositions across different genres. Another technique is to find an “energetic” section and loop that at an uneven loop length, creates an illusion that the music doesn’t resolve frequently and this creates extra tension for the listeners.

ANGRY

As with tension building in Western music, the representation of “angry” music is traditionally represented by fast tempo and lower register instruments playing slower progressions, while higher register instruments play staccato type phrases. A representation of chaos in some ways. In a more modern context, the invention of distortion and the use of the tritone by the heavy metal godfathers Black Sabbath set the tone for many sub-genres of angry music. One of my personal favourites is Industrial music, and some standard production techniques include the sampling of industrial machinery with slow and heavy drums accompanied by distorted guitars also playing slower rhythmic “chugs” using the palm mute technique.

I embraced the production techniques of the Industrial genre and applied distortion to my half time programmed drums. As this genre calls for a very mechanical feel, the pattern was hard quantised with no swing applied to the drums. I also used some mechanical sounds that were looped to help create an acceptable aesthetic for the genre. Lastly, I used a string sound that was also distorted to play a type of melodic phrase and enable some movement in the piece.

Findings

Background

In order to gather data for the evaluation of the effectiveness of the application, it was shared via social media on the 27 October 2019 and I drew the last set of data for analysis on the 12 November 2019. The app was shared through me and my partners’ personal networks. As we have school-aged children and a network of similar households we knew that we would reach a sufficient number of participants in my target age group.

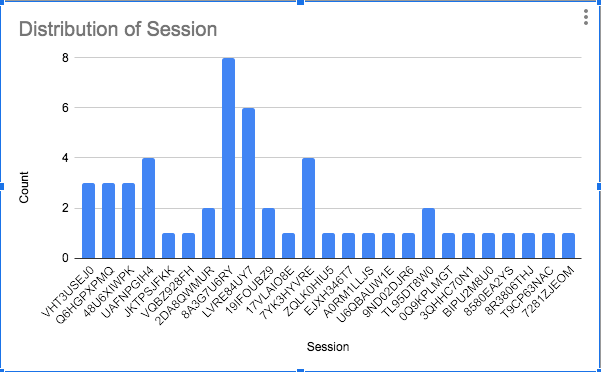

In 21 days we had 205 interactions with the application, which I consider to be a fair sample size considering the timeframe and the limitation of the personal networks through which the application was shared. This process was purely heuristic and the aim was to test the interest and usability of the application. Therefore my approach to the evaluation of the application was based on a playtest which included frequency of use and exploration as major factors.

Engagement across age range:

Finding 1

The majority of users were Over 18 (44%)

Discussion

As is personal practice in our household, particularly when dealing with children in the age ranges of 7-12 there is a process where parents would normally check an application before they “allow” their children to play or download it. So it is no real surprise that this category had the highest number of interactions. In fact when we look at the Under 7 and 7-12 categories added together it closely matches the number of the Over 18 group. This would indicate that all parents had a go of the application at some stage.

Future Considerations

This phenomenon has raised an opportunity in the fact that I could explore a similar product for the adults, perhaps change the musical themes or create a relaxation type exercise that could help adults with some much-needed self-help and relaxation time. The inclusion of some research and resources around wellbeing and exercises to help children could also be very helpful. Another possibility could be to share the results from the musical journey with the parents and they could keep a digital diary to track patterns of emotions over time.

Finding 2

There was a large number of Under 7’s who participated (30%), [fig 28] and they had the highest rate of frequency. (Fig. 29)

Discussion

As shown in Fig 28. it came as somewhat of a surprise that such a huge number of participants in this subgroup, 30% of the total sample size, used the application and more so that they showed the highest rate of frequency for using the application. They had an average of 2.08 interactions but as Fig. 29 shows there are several users who interacted three, four times with two others completing six and eight sessions each. One hypothesis could be that it was just a random occurrence due to the fact that we have a large number of children in this subgroup within our network of friends, but perhaps my simplistic design and use of primary colours were the reason for the higher number of return interactions.

Future Considerations

Two factors should be considered in this regard, Firstly if the design and interaction are too simple for my actual target group, I will need to reconsider a more challenging and interactive experience to engage them. In fact, it has to be mentioned that my youngest stepdaughter (Ursa) was not that impressed with the “game” because nothing apart from music was happening. She was expecting a more interactive experience and this should be a consideration for future versions.

The second factor is that if the design and layout are in fact more relevant to the under 7 groups, I should just focus this version towards them. I would, however, research the musical elements and establish if the current musical content is appropriate for them

Evaluation of user Experience

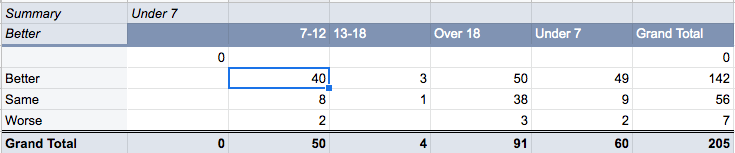

In Fig. 28 we can see the overall data set from all respondents, they are split into the different age groups and the result post-interaction. As mentioned earlier in this document the implementation of a measurement set where we gave the options of Better Worse or Same was to establish the result of the emotional/wellbeing interaction. I aimed to measure a variation in the users’ emotional state after interacting with the application and also to investigate how they interacted with the musical elements by evaluating the Journey Map.

Findings

The great majority of users indicated a better emotional state post-interaction (69%), with a major variation for Over 18’s

Discussion

When looking at the results of the subgroups there is a clear pattern of majority of the participants indicating a feeling Better after interacting with the application. This is obviously a great result and I am pleased that the application has shown some promise in terms of its main purpose.

Interesting to note how different age subgroups experienced the application as

- 82% of the Under 7’s,

- 80% of 7-12’s

- 75% of 13-18

- 55% of over 18’s

I feel that the low number of Over 18’s feeling better could be due to the participants not relating to the music, Adults would have a much richer and complex pallet for music and interactive experiences and I believe that this application is definitely situated under their normal expected interactions and could therefore not have been as successful as with the Under 7’s for example that showed a very high rate of feeling Better.

Future Considerations

As this program is aimed at a younger audience and as discussed in earlier findings, I wouldn’t aim to engage with an older audience on this platform. I would rather explore an add on service that could be beneficial to the parents and assist them with their specific emotional and wellbeing needs.

Analysis of highest frequency user

Finding

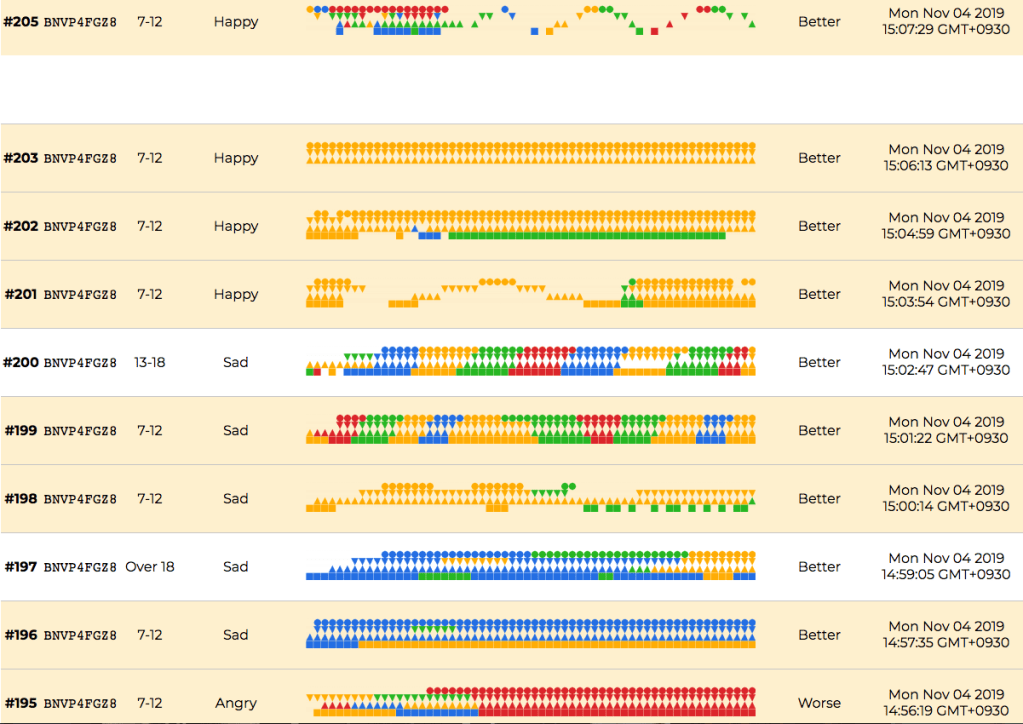

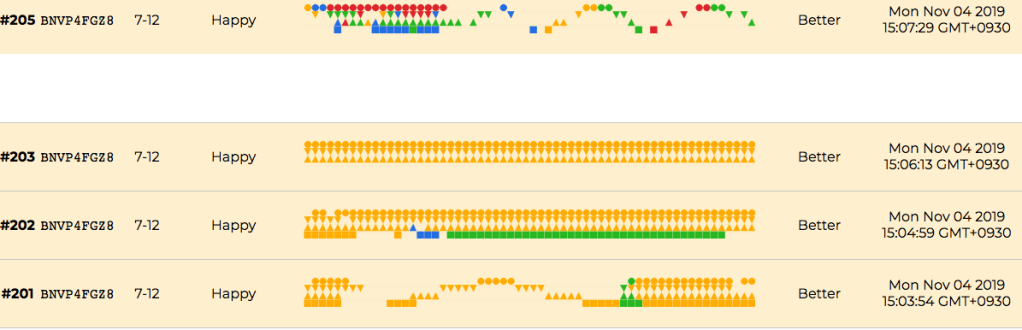

User BNVP4FGZ8 had the most number of interactions and showed some interesting variations in emotional state and outcomes.

Discussion

This particular User interaction is quite unique and if we look at the user’s Journey Map we can see how they were playing predominantly from the “Angry” category after stating that the felt Angry. They then moved to feel Sad and played predominantly Sad Music.

There is a switch to the “Over 18” age category. When analysing the time difference between the sessions it is plausible that someone else could have taken the device to also have a go. When analysing the timestamps it seems that the device was giver straight back to the 7-12 yr User, who then experimented a bit more with the different emotional states after which they started focussing more on the “Happy” emotion and this includes a session where they selected 13-18 as their age. These are obviously all assumptions and there is a great chance that all the interactions were by the same user experimenting with the different age options.

It is also worth noting how on the last interaction the user seems to be creating a pattern with the Journey Map and little regard was taken for the musical cohesion. This will be explored more in the next finding.

Future Considerations

Upon reflection, I feel that it would be a natural occurrence for any user to select all the available options (except younger) to experiment and establish whether the interface changes at all for different age groups. I think this is a great indicator for the inquisitiveness and exploratory nature of the younger user groups. I could perhaps encourage this phenomenon by adding in another layer of randomisation to encourage exploration. Perhaps the introduction of colours to determine different sonic themes.

Creating patterns instead of music

Finding

Some users started using visual feedback from the Journey Maps to create patterns.

Discussion

A phenomenon which came as a great and very pleasant surprise was when I noticed how some users created patterns normally representing a simple Sine wave. Creating the sine wave would have been a fairly simple but very deliberate exercise, as only one musical element will be triggered at a time.

Future Considerations

When observing this phenomenon from a design ethnography angle we can note answers to several questions raised in other findings. What are the natural patterns of interaction for different aged users? How do we make the application more interactive for the 7-12 year sub-group?

I could implement an interaction where the user either has to mimic the visuals, think of a Guitar Hero type experience or where they create a freeform visual that then translates into a song. in terms of gamification, this journey could be implemented in other gaming formats perhaps as a treasure hunt or problem-solving.

CONCLUSION

As shown throughout this study, the cultural, social and clinical effect of music is well documented and researched, but due to the subjective and personal experience, it is virtually impossible to conclusively assign certain emotional effects to specific sounds. It is worth acknowledging again that some users may not experience or interpret the music in the same emotional classification I assigned them, however, I was interested to see how people interact with these different emotional states and whether the musical experience could have a wellbeing impact on the users, via the measurements and results of the Feeling Better responses. My application aimed to create a generic musical experience that would be assigned to an emotional state and the user would reflect after the experience whether they felt Better, Worse or the Same

Interactive technology and mobile connectivity make web-based application fairly accessible to a global audience and this informed my decision to create a web-based application. During the testing phases, the application was shared via social media and the application had ~200 interactions with some really good feedback and positive results. I have analysed the data in more detail in the Findings page. Some of the feedback included a longer interaction time, which unfortunately was not viable due to time and financial restraints. Overall the interaction design was well received with all feedback indicating that the interface was well laid out and self-explanatory, even for users aged lower than my target audience. I believe that the use of primary colours and basic shapes which aligned with the design principles researched was a good indication of engagement, in fact as mentioned earlier it had a greater effect on the Under 7 sub-group than I had anticipated.

I was fortunate that I had a fair-sized response sample (n=205) across four different time zones which is good considering the organic means of sharing and limitations of time and personal networks. I have had some very positive feedback from speaking with people in educational and clinical roles, the value of the application and the interaction as wellbeing and a creative tool seems very logical to most teachers and parents and most were quite excited about my application.

Overall I am happy with the way people interacted with the application, It would have been great if I had more frequency from single users but it has to be noted that the session ID is dependant on the IP address and if a user had cleared their “Cookies” they would be assigned a new IP address and subsequently a new Session ID. This also posed a challenge in a household where several children or adults may have used the app. The age group differentiator at the start was my attempts to try and counter this but if there were several kids in the same age group this would have been superfluous.

There does seem to be a clear pattern in the way the different subgroups interacted with the application and this can be seen in the journey maps, this was the sole purpose of this feature and I am very happy that I integrated it into the application. One can see how the younger groups seem more adventurous or spontaneous, diving straight in and playing different sounds together. The older groups tended to spend more time testing it out before they explored multiple sounds played together. These observations are supported by my research and it shows how adventurous younger groups of users naturally are.

Some other interesting observations are that some of the younger users started interacting with the visual “journey” map and created patterns. Personally I think this is a great indication of how UI can be developed through visual feedback.

Most users indicated that they felt better after the session but it also became clear that users were deliberately testing other emotions to see whether the interaction changes. Some users also reported back on their favourite sounds, isolating them to a single element within an emotion. Even though this is not in line with the intended outcomes, this observation of a positive association could indicate successful wellness outcomes for the project.

Musically, I aimed to keep the aesthetic of the music more contemporary. I referenced more cinematic production techniques to create an emotional association, and I think this has translated well into an overall general sound with distinct emotional direction. Initial feedback again confirmed how peoples interpretation of sound is a very personal one where the Angry and Worried sounds were interpreted as excited or happy. The feedback about creating a longer experience may have yielded some interesting data relating to people experimenting more with these different emotional states and relating the sounds to the emotions.

I observed that 69% of the total users indicated a positive emotional outcome after interacting with the application. This is a great outcome for the emotional wellbeing aspect of the project, but on the flip side, 75% of users only interacted with the application a single time. This is not a great result for the User Interaction and design aspect of the project. A possible reason for this is that in the context of the project being shared it could have been understood that this was just a test. There was no incentivisation for children to test the application, we purely shared and asked parents to share it with their children as a way for me to test the program. This may have led to people only interacting with the application once to see if it worked. If the application progresses into a stand-alone application there may be a slightly different use ratio., especially if it is used in specific situations or prescribed by a parent, teacher or therapist.

In terms of the emotional connection and regulation of the application, I think it is safe to hypothesise that there was clear evidence of an improvement in emotional wellbeing (69%) and that the application contributed to a positive change in emotional wellbeing, It must be noted that the whole experience would have contributed, not just the music or the User experience. Therefore I may conclude that regardless of the musical alignment the action of interacting with a musical tool showed a positive emotional and wellbeing outcome for most users.

As a first step in continuing to develop the program, I will share the application and reach out to other educators and therapists to get more feedback and data. Perhaps explore the possibility of using the application with a closed focus group over a period of time.

Appendix

This page provides a quick reference guide to the terminology used throughout this research. Its purpose is to clarify the use of terms and establish consistency of meaning with regards to new or contestable terminology.

Term – Definition

ASD

Autism Spectrum Disorders are brain conditions that result in people learning in a different way to others. They might face challenges in how they recognise and respond to things and how they respond to emotions. People living with autism may be non-verbal or may talk a lot, and their senses might respond differently to those of other people. For example, someone living with autism might hate touching things – or they might love touching things that they shouldn’t. (Novita, 2019)

Adobe

A software development company that creates industry-standard popular design and illustration programs like Photoshop and Illustrator.

DAW

Digital Audio Workstation – software program used to edit, arrange and mix audio content.

Neurodivergent

A term for people who display non-neurotypical behaviours and may have had a diagnosis.

Ableton

the DAW I used for music production

UX

The user experience (UX) is what a user of particular product experiences when using that product

UI

The user interface (UI) is everything designed into an information device with which a person may interact.

Musical Scale

A scale is a sequence of small intervals – in Western music, those intervals are usually tones (whole steps) and semi-tones (half steps).

Musical chords

A chord, in music, is any harmonic set of pitches consisting of multiple notes (also called “pitches”) that are heard as if sounding simultaneously

Diminished chords

Diminished chords, also known as diminished triads or dim chords, are dissonant chords that combine a root note with two minor thirds above the root.

Staccato

“Staccato” is a form of musical articulation. In modern notation, it signifies a note of shortened duration, separated from the note that may follow by silence.

Palm Mute

The palm mute is a playing technique for guitar and bass guitar, executed by placing the side of the picking hand below the little finger across the strings to be plucked, very close to the bridge, and then plucking the strings while the damping is in effect. This produces a muted sound and is also referred to as a “Chug”

Heavy Metal

Heavy metal (or simply metal) is a genre of rock music that developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, largely in the United Kingdom. With roots in blues-rock, psychedelic rock, and acid rock, the bands that created heavy metal developed a thick, massive sound, characterized by highly amplified distortion, extended guitar solos, emphatic beats, and overall loudness. The genre’s lyrics and performance styles are sometimes associated with aggression and machismo.

Industrial Music

Industrial music is a genre of music that draws on harsh, transgressive or provocative sounds and themes. AllMusic defines industrial music as the “most abrasive and aggressive fusion of rock and electronic music” that was “initially a blend of avant-garde electronics experiments (tape music, musique concrète, white noise, synthesizers, sequencers, etc.) and punk provocation”

Elements of the Production process:

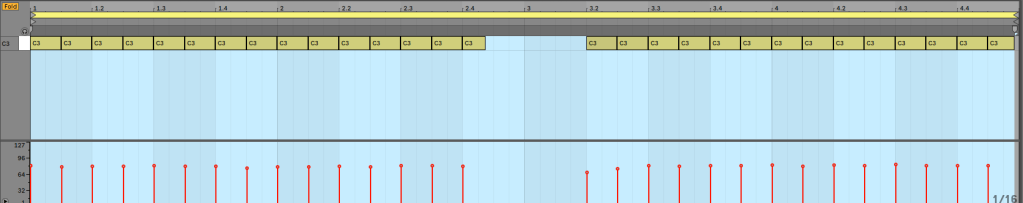

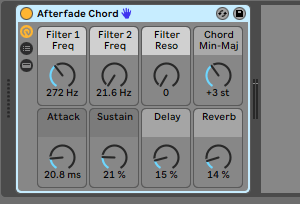

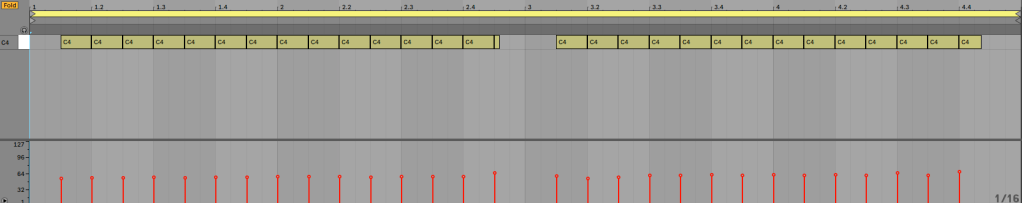

This section provides screenshots of the Instruments, Midi, audio waveforms and effects chains of the different elements that make up the compositions within the musical component of this project.

Final Production:

Happy:

DRUMS:

LEAD

The first chord progression is used as the main melodic element with the second loop creating more energy to create a happy exciting aesthetic.

BASS

TIMBRE

I used some arpeggiated high register notes to create a happy tone, and decided to create 2 versions and pan them slightly LEFT and RIGHT to create a wider stereo image and movement.

SAD

DRUMS

BASS

LEAD

TIMBRE

WORRIED

DRUMS

BASS

LEAD

TIMBRE

ANGRY

DRUMS

LEAD

BASS

TIMBRE

https://soundcloud.com/locojo-1/playme-suf-example

First Prototyping and interaction experiment

List of References

Ali, E. (2018) Turning the mind inside out. (PIXAR Inside/out) Retrieved from https://www.bibalex.org/SCIplanet/en/Article/Details.aspx?id=12336